Efficiency and Resilience

We are expected to believe that the cause of the West's water troubles has been definitively diagnosed. Inefficient water consumption has led to too much wasted water. The solution is simple, even if it is not exactly easy due to the various political snags that have grown up around the way things have always been done. We have to use water more efficiently.

This is a difficult idea to dislodge from people's minds, partly because it is inarguable that water here is wasted in one way or another. How does one defend flood irrigation on alfalfa fields or golf courses in the desert or extravagant water fountains at Las Vegas casinos? (The answer: very carefully. Public golf courses can represent valuable green space in urban settings, and the Bellagio's fountains use salty well water; Las Vegas is very strict about water conservation. I'll get to alfalfa below.)

The goal of the Progressive Era conservation movement was to make efficient use of resources to bring about the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Scientific management was necessary in order to do that, they believed. The belief that experts should guide the allocation and maintenance of the country's resources formed the basis for that era's "gospel of efficiency," according to historian Samuel Hays in a classic work on the topic.

Yet Hays identifies a few questionable aspects to this admirable goal. For one, the reliance on expertise threatened to trump democratic processes, since more weight was given to science than the whims of majority opinion. This contrasted with some of the movement's messages about representing the will of "the people" against business interests--messages reproduced in subsequent decades by sympathetic historians. Hays points out that multiple competing perspectives claimed the same mandate, and the Progressives supported corporations at times. For example, President Teddy Roosevelt, the famous trust buster, believed that some trusts should be preserved because the arrangement was more efficient than allowing multiple firms to compete. Additionally, the gospel of efficiency could sometimes extend into absurdity. Hays recounts how the president of the American Society of Civil Engineers repeated how Lord Kelvin responded to seeing Niagara Falls, which he identified as the response of "a true engineer:" "I consider it almost an international crime that so much energy has been allowed to go to waste." The conservation movement was at times a tug of war between the utilitarian goals of engineers and the more romantic desire of naturalists and outdoorspeople, but the flooding of the Hetch Hetch Valley, near Yosemite Valley, for the sake of San Francisco's drinking water marked a kind of triumph for the utilitarians.

The New Deal era saw a certain version of the conservationist ethic translated into the form of public works programs. President Franklin Roosevelt, at the dedication of Hoover Dam (Boulder Dam at the time) said:

To divert and distribute the waters of an arid region, so that there shall be security of rights and efficiency in service is one of the greatest problems of law and administration to be found in any Government... We know that, as an unregulated river, the Colorado added little of value to the region this dam serves... The mighty waters of the Colorado were running unused to the sea. Today we translate them into a great national possession... The people of the United States are proud of Boulder Dam.

The federal government's Bonneville Power Adminstration hired Woody Guthrie to write an album's worth of songs praising the Grand Coulee and Bonneville Dams on the Columbia River in similar terms: the dams harnessed the underutilized power of the river to generate electricity, create jobs, and provide water for farms for hard working Americans.

These same dams became a prime target for twentieth century environmentalists. The Bureau of Reclamation's lightning rod commissioner Floyd Dominy became an arch-villain. But historian Ian Robert Stacy calls Dominy "the last conservationist," an assessment that I agree with. Dominy's personal history as the child of Nebraska homesteaders and his early post as a Wyoming field agent popular with the locals for his promotion of dams led to a personal crusade for developing the water resources of the West, but his dubious methods did not escape notice. By the time the revisionism of twentieth century environmentalists had sharpened into focus with Marc Reisner's Cadillac Desert in 1986, the verdict was clear: government bureaucrats and their engineers had betrayed the public interest.

This was a fitting critique for the nascent neoliberal era. Efficiency was still the goal, but government bureaucracy was wasting resources just as it wasted tax dollars. The solution (presented tentatively) was markets and private investment. Reisner writes in the afterword of the 1993 edition of Cadillac Desert, "If free-market mechanisms... were actually allowed to work, the West's water 'shortage' would be exposed for what it is: the sort of shortage you expect when inexhaustible demand chases an almost free good." Reisner went on, in the late 1990s before his untimely death, to become an agent for a company trying to build a private water bank in an underground aquifer--intending to store water in times of plenty and selling it in times of drought. Many of his cohort protested, but the Wall Street Journal reported that, on the other hand, "many of Mr. Reisner's old environmental colleagues welcome a private market." From the WSJ: "'I don't have any great love' for business executives, says Tom Graff, an attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund in Oakland, Calif. 'But our basic view is that private action -- with all its wants -- is positive.'"

I propose that it is not the incompetence and corruption of bureaucrats that has caused our water troubles but the intrinsic problems that come with the goal of efficiency. Put simply, perfect efficiency exists in tension with resilience. If markets perfectly allocated every drop of water in the West to its highest use, people's livelihoods and lives would structure themselves around those uses, only to require painful and unpopular shifts when the amount of water inevitably changes. Human life is inefficient that way. We like to rest and play and hang out when we are not working, so our wages have to support us when we are wasting time doing those types of things. (I wrote here about some of the history of the region's attempts to rationalize labor, partly by maintaining a race-based dual labor system.)

Perfect efficiency can tolerate neither scarcity nor surplus. Adherents to the conservation movement's gospel of efficiency built dams to solve the former problem and neoliberal markets are supposed to solve the latter. "Unfortunately, there's plenty of water for 150 million Californians... There's too much water in California, not too little," said Marc Reisner in an interview in 2000.

We are all used to talking about Western water as if it is scarce (I am guilty of this), but it would be more accurate to say that its "problem" is its dynamism. Craig Childs points out that there are "two easy ways to die in the desert: thirst and drowning." The climate is alive; water is alive. Investment demands that the future be reasonably predictable, so this living system must be converted into resources by extracting and separating the parts of this vast web in a way that they can be quantified. Making use of water is not wrong or sinful; it is inevitable as long as humans drink and eat and go swimming. But the case for maximum efficiency demands water's commodification and either begins with the assumption that that conversion has taken place or that natural resources already exist intrinsically in that state of being, which is obviously false.

I think there is a prevalent mentality that our system of reservoirs is like a checking account, and the easily intuited solution to overspending is that we need better budgeting. There are two problems with this view. The first, as I've mentioned, is it takes for granted the process of converting water into a fungible commodity. (Think of all the forms that water takes: rain, ice, fog, rivers, ponds, springs, aquifers, brine, mud, etc.) The second is that it misapprehends the purpose of this vast water bank. The bank was built to make loans, not to maintain a checking account. The respective logics are antithetical. It would only make sense to balance our account, to manage our water for maximum efficency, if we lived in a political economy that tried to distribute resources equitably rather than develop and exploit them for private profit. Seen that way, it is very odd to deploy free markets to solve this problem--unless the real problem is that our resources are too accessible to the public.

Efficiency and resilience exist in tension; which is to say, we should consider that the places where we see inefficiency in water use may indicate an adaptation to unpredictability. The most recent (2016-2020) Consumptive Uses and Losses report for the Upper Colorado River Basin finds, "It is estimated that in an average year, about 37 percent of the irrigated lands in the Upper Basin receive less than a full supply of water--either due to lack of distribution facilities or junior water rights." While recognizing that some portion of that figure is due to "lack of distribution facilities," which I read as indicating that some farms only have "paper water," it is remarkable that, potentially, a third of farms in the Upper Basin do not receive a full supply of water--senior rights holders enjoy their full share while junior rights holders experience the brunt of scarcity. Seen one way, this speaks to how much greater demand is than supply. But seen another way, the fact that federal project water can routinely leave such a significant number of people dry without sparking rebellion could be something to admire.

Western water writer John Fleck argues that alfalfa agriculture, now demonized for half a century, actually supports the resilience of regional water use in three ways, going so far as to state that "it's better to view alfalfa as part of the solution." Alfalfa is resistant to drought, easy to move (meaning that it can function as "virtual water" to serve shortages more easily than wet water), and relatively low value. Many have taken issue with alfalfa on that last point, but Fleck points out: "When water becomes scarce... alfalfa is often the first crop to be fallowed, shifting water either to municipal users or to other, more valuable crops. It is a simple buffer if we offer farmers some benefit in return for relinquishing some of their irrigation water."

None other than Marc Reisner eventually found something to like about "wasteful" Western agriculture. In his 2000 interview referenced above, he stated:

I was one of the first to argue that irrigation is a very inefficient use of water on a per acre per dollar basis, but if sprawl is what you get by moving water out of agriculture, I think I'll stick with alfalfa. There are arguments to be made for those low-value crops. Rice, for example, is a pretty good substitute for the wetlands that used to be there before the ricelands. You could make a similar argument about alfalfa, which is now everybody's most hated crop because it uses more water per acre than any other. It's probably second only to rice in its dual-purpose importance as wildlife habitat. So do you really want to get rid of every last acre of alfalfa?

(See also his 1997 article in High Country News, where he elaborates on the benefits of ricelands as wildlife habitat.)

Alfalfa agriculture represents adaptation to the arid West not just in its qualities as a deep-rooted legume, but as an adaptation to the vagaries of markets. Agriculture is sensitive both to drought and abundance; overproduction threatens to drive prices down and bankrupt farmers. Historian Mark Fiege in Irrigated Eden tells how southern Idaho farmers started planting alfalfa as a cash crop in the 1910s. By the following decade, combined with a broader agricultural depression, alfalfa prices had plummeted. The solution was more cows. Between 1919 and 1924, milk production expanded by 50 percent. One farmer in 1924 said, "'We have got ten thousand cows and are now milking our way out' of the excess alfalfa problem." As someone who hates animal agriculture, partly because cattle are an especially inefficient way of getting calories that humans can eat, that same inefficiency means that dairy cattle can easily absorb any overproduction of alfalfa and stabilize its price. People love beef and dairy, and that reliable demand has helped a very dry region poorly suited to agriculture find a way to survive as water and markets ebb and flow around it.

These days people wonder why farmers don't just grow higher value crops. The simple answer is that they used to, but now that soil is largely growing ornamental turf in subdivisions. Utah County had plenty of orchards (some are still there) before the federal government built the Geneva Steel plant for the World War II war effort. As people increasingly went to work in the factory, orchards became suburbs. The West is not exactly known for abundantly fertile soil, and every housing tract has pushed farms out onto increasingly marginal land. Fruits and nuts get higher prices than alfalfa, but they are also more capital intensive and more sensitive to drought; it takes several years from planting to get mature trees, and in dry years, any available water needs to be directed toward those trees to keep them alive, even if conditions will make for a poor harvest. If a farmer is wondering if his commmunity will be overtaken by sprawl in ten years' time, it would be foolish to plant an orchard. Alfalfa, on the other hand, is a perennial that only needs to be replanted every decade or so, requires little investment, and, while it is low value, it can keep one's water rights parked until it's time to sell the property.

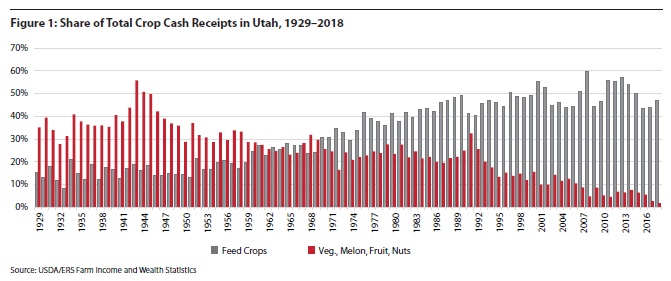

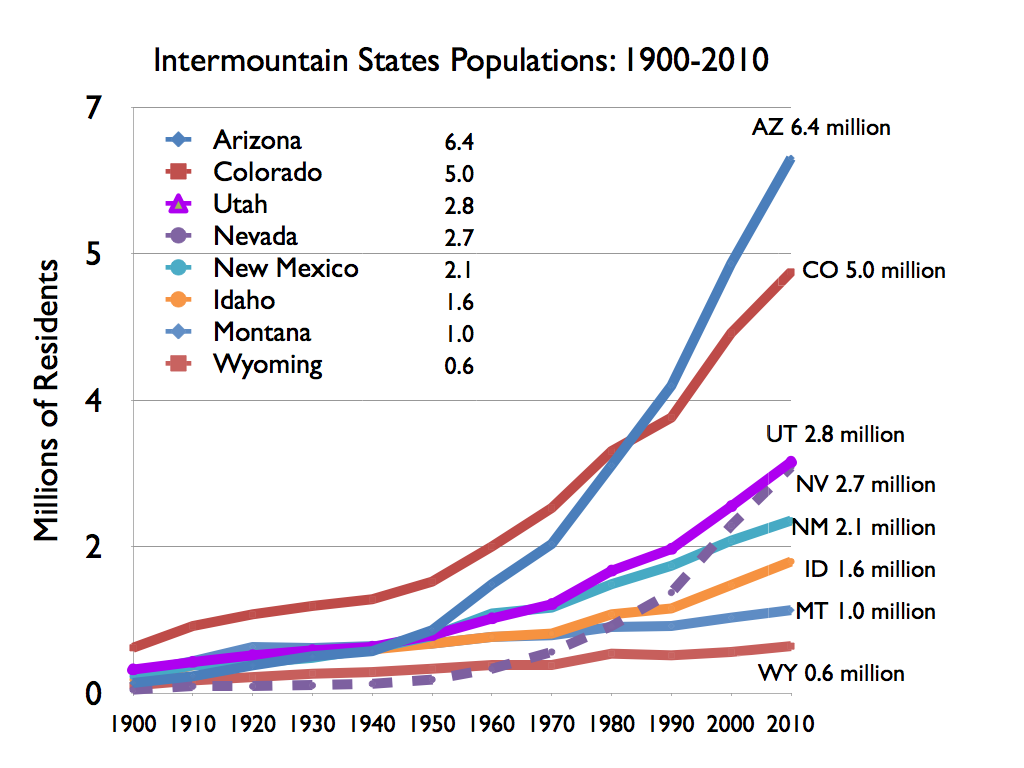

Consider this graph of alfalfa's (feed crops) growing dominance in the agricultural sector versus the state's population growth below. (Utah has not grown as rapidly as Arizona or Colorado, but has grown rapidly nonetheless.) Alfalfa agriculture is not just compatible with the wide swings of environmental conditions; I believe we could say it is also compatible with the churn of real estate development, more so than higher value crops that may require more investment or specialized skill to grow.

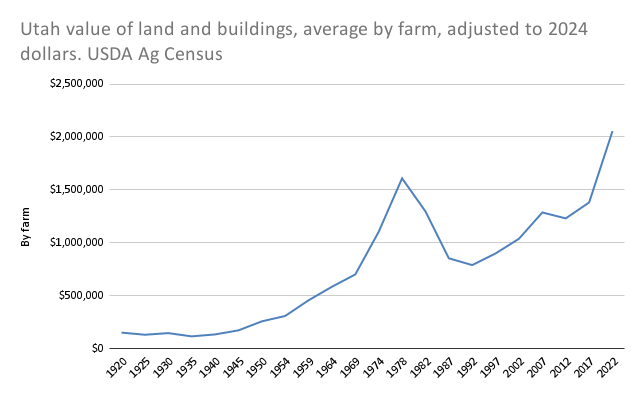

This may be a bit of a tangent, and I admit to not fully understanding the causes of the 1970s farmland bubble, but here is a chart (created by me from USDA data) of agricultural land and asset prices in Utah, adjusted for inflation. My understanding is that inflation and overseas demand for grain--and potentially the oil crisis and government credit--led to a spike in the value of farmland, which "corrected" by the mid-1980s. This is related to discussions of value in agriculture, but I included this here because it illustrates the real world logic of markets. Fickle and irrational forces require that we turn the living world into a pool of resources that can suit their whims, toward the only goal that matters: giving capital a return on its investment. Here's hoping you are lucky enough to buy the dip and sell at the top.

There is a fundamental problem with this system, where a political-legal-economic framework expands over land, minerals, water, flora, and fauna to convert them into resources--raw materials to be converted into money. The problem is that money cannot be converted back the other way. Yes, technically it is possible to desalinate or distill water, pull carbon out of the atmosphere, and engineer synthetic foods. But the costs associated with these things are so high as to make the initial conversion pointless. On some level, I think we all have an intuitive understanding that we are hopelessly underwater on a loan so big that the consequences of default are existential.

To an extent, I am critical of the line of thinking that I am advancing here. Many expressions of it are puritanical; I don't believe that the luxury and indulgence of ordinary people requires a catastrophic reckoning. But at the same time, we can recognize a Ponzi scheme when we see one, and it is possible to organize an appropriate, collective response rather than self-flagellate.

Another reaction to this state of affairs, which can only be either cynical or naive, is to imagine that some clever strategy will convince God or Providence or Nature to forgive the debt, ushering us into a state of being outside of time (how else can a thing that goes up not come back down?). This sinister, reckless optimism flows like an underground river beneath the history of American capitalism, pushing up into surface springs periodically, manifesting in the idiom of the day. In the mid-late 1800s, the ideology of Manifest Destiny went searching for a way to transform the Great American Desert -- or, at bare minimum, to assuage the fears of would-be settlers that the vast speculative scheme of privatizing the public domain might collapse on them. What it came up with was "rain follows the plow."

That optimism flowed into the Progressive Era, out of which came the Colorado River Compact. The Reclamation Service's first director, Frederick Newell, wrote in his 1906 book Irrigation in the United States, "The dead and profitless deserts need only the magic touch of water to make arable lands that will afford farms and homes for the surplus people of our overcrowded Eastern cities, and for that endless procession of home-seekers filing through the Castle Garden." The idiom at that point was one of engineering: scientific measurements and the building of high dams would tame and rationalize the climate into a force that we could depend upon and use, just as steam engines harnessed the power of water. The result was the overallocation of the Colorado River System. As late as 1960, one of the priests of scientific management reaffirmed his optimism. The Supreme Court appointed a lawyer, Simon Rifkind, as a special master to help the court with a lawsuit between Arizona and California. California was using more than its allocation, piping that extra water to Los Angeles's Metropolitan Water District. This did not cause immediate problems, however, as the Upper Basin was using far less than its allocation. Once the Upper Basin grew into its share, Rifkind recommended that California bear the shortage, but he was supremely confident that that day would never come. "I am morally certain that neither in my lifetime, nor in your lifetime, nor the lifetime of your children and great-grandchildren will there be an inadequate supply of water for the Metropolitan Project." The court endorsed Rifkind's analysis, and its ruling in 1963 represents yet another missed opportunity for the Colorado River Compact to be brought into line with the real world. (The Department of the Interior required California to cut its consumption forty years later in 2003.)

In the neoliberal era, it is appropriate that this sinister optimism would manifest as a creed that it was the government experts and bureaucrats who led us astray from the gospel of efficiency. Government, we all know, is inefficient. Markets are the antidote. In time, the idea that the efficiency of markets can discharge this grand debt will appear as fanciful as the idea that planting trees on the plains can create a wetter climate.

PS if you think that we should try to solve the problems of capitalism by opening new land for settlement by subsistence farmers, I'd say we already know how that ends!

(Check out this Left Anchor podcast episode with Zak Podmore and Marshall Steinbaum for more about Cadillac Desert as a reaction to the New Deal.)

References:

Samuel Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959).

John Fleck, Water Is for Fighting Over: And Other Myths About Water in the West (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2016)

Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water (New York: Viking, 1986).

Mark Fiege, Irrigated Eden: The Making of an Agricultural Landscape in the American West (Seattle: University of Washington, 1999).

Frederick Newell, Irrigation in the United States (New York: T. Y. Crowell, 1906).

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

Racism in Environmentalism and Why it Matters