Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

How do we make sense of contemporary water shortages? This post will draw on more in-depth posts that treat the last 50 years or so of water in the West to arrive at a conclusion. For a critique of the idea of water flowing uphill toward money, go here. To read about the political economy of alfala, that's here and here. Water activism here in Utah in the 1970s and '80s kept Great Salt Lake on the margins. Finally, to read about water marketing, you can find that here.

To paraphrase Homer Simpson, western expansion is the cause of, and the solution to, all of the country's problems. Or, in a more academic phrasing, "Expansion became the answer to every question, the solution to all problems, especially those caused by expansion," according to Greg Grandin in The End of the Myth. Robert O. Self writes, "Behind boosters is the most interesting feature of western cities: urban growth as an end in itself, an economic logic fundamental to capitalism, was elevated by western boosters to the level of civic religion... Boosters in western cities were enormously important to a critical process: attracting the eastern and midwestern capital and migrants necessary for urban survival." Greg Grandin is referring specifically to Thomas Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase, though the whole book examines the ways that expansion, in modified forms over times, has continued to inform American capitalist ideology. For Grandin, the rise of Trump, and the border wall that he made central to his 2016 campaign, indicate that our ideological fixation on expansion has finally run its course. Along those lines, I contend that at some point the country will exhaust the material bases of expansion--land and water--and face a reckoning that will parallel the country's political shift toward a viciousness that rebounds inwards. Maybe we are at that point, but it is hard to say.

I propose a corrective to the singling out of agriculture as the cause of the West's water shortage. The instagram account @westernwatergirl recently posted a slate of memes that envisioned a paradise in various scenarios, one of which portrays "The Colorado River Basin if the US just banned the export of alfalfa." It's a joke, and the other memes should reinforce the idea that there is not a magic bullet. But in the comments she notes that "cities only consume like 20% of the water here." I have noticed that many people here in the West have focused on agriculture's water consumption to the exclusion of increased municipal and industrial consumption. None other than Marc Reisner, in Cadillac Desert, wrote, "California has a shortage of water because it has a surfeit of cows--it's really almost as simple as that."

This is where expansion has been so politically useful. Just as a "free land" policy in the last half of the 1800s eased conflict between capital and labor, "free water" has arranged city and country into a formation where, despite differences, they have been pulling in the same direction. But there have also been times when the rifts manifest-- urbanites cried foul over the amount that the federal Bureau of Reclamation put toward irrigation projects during the 1970s when budget deficits and stagflation made the country fiscally conscious. Now, as we are seeing the effects of megadrought on the water supply, urban water consumers are once again trying to lay the blame on agriculture.

There is an inescapable dynamic in contemporary water discourse. It is true that many city dwellers (like myself) want enhanced conservation so we can leave more water in its natural channels. But there are also officials who can take advantage of this positioning in order to simply direct more water toward cities without leaving much left over. ("Water shepherding" is the term for making sure conserved agricultural water makes it all the way downstream to Great Salt Lake.)

Activists from an earlier generation identified the way that water project boosters used the aridity of the state to build support for water development. A member of the Coalition for a Responsible Central Utah Project (CRCUP) wrote about one of the "dangerous myths" about Utah's water: "Utah needs the Central Utah Project (CUP) or it will dry up and blow away." In fact, he wrote, "Utah is blessed with abundant supplies of water." Utah Rivers Council still needles the "water buffaloes" of Utah on this point, writing on their website that "water project salesmen ignore inexpensive alternatives to their pet porkbarrel projects using fear and sowing ignorance about our water supply." In other words, promoters of water development know that most people respond to the idea that we are running out of water by treating it as a supply problem. We are growing, therefore we will need more water. We have a long history of meeting the problem in that way, after all. The opposition responded by saying that we do have enough water to meet growth, therefore we do not need to augment the supply.

Making sense of this situation is nuanced. It is true that the water buffaloes' main talking point is the region's aridity. A 2015 Utah state government audit found a number of inaccuracies in the Divison of Water Resources's estimates for future water growth. The audit effectively confirmed the charge of critics that the agency was overestimating the potential for water shortages (though it did not indicate that their purpose was to bolster support for water development projects, as critics claim.)

But then what do we about unsustainable water consumption on the Wasatch Front? For the CRCUP activists, they recommended sources of water that would not come from the Central Utah Project, including diverting more water from the Bear and Weber Rivers and pumping groundwater. These alternative sources, if pursued, would have lowered the level of Great Salt Lake. Environmental activists and stream fishers ultimately supported the Central Utah Project Completion Act of 1992, since there was very limited objection to the idea of growth in the state or the idea that water was necessary for such growth. With the CUP (nearly) completed, the water buffaloes are looking to build additional dams on the Bear River, something which the previous generation of environmentalists had recommended. (To be clear, Utah Rivers has long been one of the most outspoken critics of the Bear River Development Project.)

The point of all this is to say that, in the big picture, there is sometimes little daylight between environmentalists and their ostensible opponents. Environmental sociologist Dorceta Taylor has a term for this approach: business environmentalism, which she defines as "an amalgam of utilitarianism, preservationism, conservationism, and capitalist interests." Some critics tend toward preservationism, in the case of the CUP critics who wanted to preserve riparian environments in the high Uintas. But there is a spectrum of business environmentalists, and many urban critics would probably find themselves in a big tent with the water planners that they think they disagree with.

Let's look at the example of wastewater reuse. This is a conservation measure: treating sewage effluent and reusing it. It is an example of the types of alternative sources that older environmentalists argued for. But wastewater currently flows into Great Salt Lake (for better or worse), meaning that reusing that water would lower inflows into the lake. Cities on the Wasatch Front want to capture this source of water, putting them at odds with the lake.

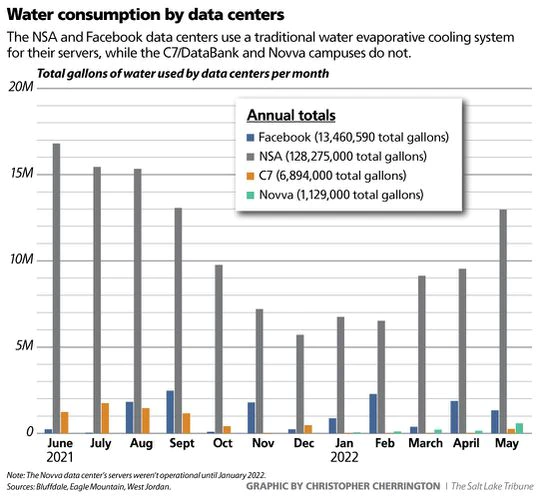

Something that I find much more concerning is the development of thirsty industries in the Great Salt Lake basin and the lack of mainstream attention toward their plans. With the help of $1.6 billion from the federal government, Texas Instruments is building a semiconductor fabrication plant in Lehi, but "the company did not say how much water the fab is expected to discard," according to the Salt Lake Tribune. In order to compete with China, the CHIPS Act of 2022 subsidizes this kind of production for fabs around the country, including in Texas, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Idaho, and Utah. Semiconductor fabrication typically uses a large amount of water--a big concern in these arid states. The indeterminate water usage of information technology facilities is a familiar story on the Wasatch Front. Facebook's expanded data center in Eagle Mountain promises to contribute to water restoration efforts and to use less water than ordinary data centers. That remains to be seen, while the smaller data center used about 41 acre-feet a year. The secretive NSA data center in Bluffdale uses nearly ten times that much, something that the town found out through a records request. Google and another data center company named Tract have also bought land in Eagle Mountain, though their water consumption plans are unclear.

A bottling plant in Salt Lake City, or a "BevTech manufacturing startup" if you speak Silicon Valley, reported plans to use 2 million gallons of water a day, more than 6 acre-feet a day, or 2,240 acre-feet a year. That plant, Vobev, has since come online, but to my knowledge there has been no follow up reporting about how much water they are using. Salt Lake City recently proposed a cap on water use at 300,000 gallons per day, but the city did not pass the measure. There is also a Niagara Bottling facility in Brigham City that draws water from a spring, but I was not able to find out how much water they are taking and exporting.

Another pressing issue is the proliferation of "inland ports" in Utah--warehouse processing centers that move traditional port activities to inland facilities. Three of these warehouse developments are adjacent to Great Salt Lake wetlands, areas that the lake's wildlife greatly depends upon. While this is not a water consumption issue necessarily -- and there is even a strong case for keeping existing farms over razing them for warehouses -- Utah Inland Port Authority is steamrolling any opposition to give subsidies to well-connected developers while threatening to increase noise and light pollution and emissions in a sensitive area. (You should get involved with Stop the Polluting Port Coalition!)

You may be thinking that Facebook using 41 acre-feet a year is not that much in the grand scheme of things. That's correct, but the problem is that we need to be cutting water consumption and letting it remain in its natural channels, not transferring it from one sector to be used in another. Farmers have reservations about being made to conserve water because they are suspicious about their conserved water simply going to urban industry, and they're right to be. For about the last half century, water planners have not been very shy about anticipating agricultural-to-municipal transfers. In that context, it is reasonable to suspect that the people making an issue over Great Salt Lake are merely coming for farmers' water. Some of them are!

Additionally, there are a couple of flaws in counting on the savings from agricultural transfers. One large one is looking at domestic water consumption and leaving out increased consumption from industry, as I've pointed out above. People moving into formerly rural areas may decrease net water consumption on those lots, but they need to work somewhere. Beyond that, industry on Great Salt Lake already contributes quite a bit to the evaporation of water directly out of the lake. Mineral extraction accounts for about 9% of total consumptive water use, roughly equal to the consumption of cities and urban industry.

Another problem is that the savings from agricultural transfers are per capita savings. At some point, enough capita's results in a net increase in water consumption. Looking at five year averages in the Colorado River basin between 1971-1975 and 2000-2005 (the most recent data for the full basin) shows that irrigated agriculture consumed 713,000 less acre-feet of (surface) water in that period. That should provide quite a bit of room for urban growth, but municipal and industrial water consumption increased by 1,068,000 acre-feet. That means a net total of 355,000 more acre-feet consumed due to urban growth.

|

|---|

| Bureau of Reclamation data, chart by author. "M&I" = Municipal & Industrial |

I hope I've demonstrated that not everything would be peachy if we just stopped exporting alfalfa. To go back to what Reisner wrote about cows in California, it is rather odd that he should land on that conclusion. One of the most impactful chapters in the book is about Los Angeles's water grab from the Owens Valley--taking water from farmers for urbanites. Indeed, if there was one inciting incident that led to the Colorado River Compact, it was that episode. His examples of water flowing uphill toward money, California's State Water Project and the Central Arizona Project, are also projects that mostly benefited cities. (There is also the flooding of the Hetch Hetchy Valley on behalf of San Francisco's urban population, which helped solidify the utilitarian slant of the conservation movement as it pertained to water.) Why are we so quick to leave cities out of the story?

Because of the way that criticism of Western water developed, there is a mindset that contributes to underestimating the harms of industry and urban development. As I've written, the ideal of the yeoman farmer subconsciously shapes our ideas about how the West should operate. But, in a similar way to how the conservation and environmental movements inverted the moral and spiritual valence of wilderness, I contend that water-focused environmentalists have simply inverted the ideal of the yeoman farmer. Historian Richard Hofstadter writes, "Out of the beliefs nourished by the agrarian myth there had arisen the notion that the city was a parasitical growth on the country." The legacy of Cadillac Desert and other critiques from that period is the idea that the country is a parasitical growth on the city. As with the idea of wilderness, we should help accelerate the synthesis of this inversion--"wilderness" defined as land unimpacted by human efforts is largely fictive, and the concept deserves to be dismantled. City and country are not in a parasitical relationship with one another, and we should view both sectors as interrelated in a more complex and more realistic way.

I opened this post by talking about expansion. I believe, as it pertains to the West, there is an irrational, even absurd, belief in growth as a virtue. This gets amplified when considering that liberalism, in the classical sense, views the enclosing of the commons into private property as a way to facilitate growth. In the neoliberal era, economic growth gets prioritized as a matter of policy under the belief that economic prosperity leads to social progress. On top of all of that, contemporary liberal and environmental discourse is inflected with an erroneous idea that computing and information technology is a "green" industry relative to manufacturing. While many people tend to map the rural-urban divide onto contemporary partisanship in a way that is often sloppy, there are in fact strong resonances between liberalism (broadly defined) and the idea that urban growth is the antidote to water waste in the agricultural sector.

Obviously this is not to say that conservatism is correct and that agriculture--whose water consumption also appears to be trending upwards in recent years, especially when counting groundwater--should be exempt from conservation. The fact that agricultural-to-municipal transfers have been leading to reduced water consumption with minimal political pushback is (most likely) a positive development. My point is that we need more scrutiny of the business environmentalist approach, because it is overly optimistic about the potential for growth to solve the problem.

Additionally, in the grand sweep of Western water history from 1862 to present, there is a tendency for capital to put investment toward making labor contingent and mobile in the West. Seen this way, Western farmers acted as a vanguard for settlement and were never meant to be permanent; eventually they were supposed to sell out to make way for cities. I've written more about this here. I have a hard time with a policy that displaces rural communities in favor of urban professional ladder-climbers who may only stay for a few years before choosing to (or needing to) move for another opportunity. Liberals see that kind of efficient market movement as a positive, but I don't share that view, partly because it's pricing me out of a city where I have all of my community and professional connections. Rural agriculture is not the antidote to the system, because they are also wedded to it. The question of what to do about all of this is a large and complex one that will have to wait for another post.

(Note: This post was updated 1/16/25 to include a quote about western boosters and a source.)

References:

Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019)

Robert O. Self, "City Lights: Urban History in the West" in A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2004)

Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water (New York: Viking, 1986)

Richard Hofstadter, "The Myth of the Happy Yeoman," American Heritage 7 no 3 (April 1956).

William Cronon, "The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature," in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature ed. William Cronon (New York: Norton, 1995).

**Read more:**

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water