What's the Deal with Alfalfa

Agriculture in the Mountain West, like anywhere else, is complex. There are inefficiencies and peculiarities, as many are now aware. About 80% of Utah's water goes toward agriculture, and that sector generates about 2% of the state's GDP. The dominant crops are some form of animal feed: alfalfa hay, pasture, or other hay. Many respond to this information by thinking that the agriculture industry doesn't make sense here -- that there must be some sort of conspiracy or corruption that has led to this outcome. I think this suspicion lends to the outsized influence of the idea that "water flows uphill toward money" (more here).

But if we change our framing and view Western agriculture as an adaptation to land, rather than being oriented primarily around maximizing profit, some of the peculiarities start to make more sense. In other words, we should realize that the farms are not there to grow alfalfa; they grow alfalfa because they're there. Hopefully that makes more sense by the end of this post.

For historians, farming is not simply an enterprise for making money by growing crops. Farming is loaded with cultural and political significance. I examine some of the ideological reasons for bringing smallholder agriculture to the West in a post here. But, of course, there are also material motivations, both for policymakers and farmers themselves. A large part of the calculus, then and now, concerned land values.

Land speculators and Western politicians largely drove land policy from the 1860s on, in the form of "boosterism." It is true that the Homestead Act depended politically on the Jeffersonian idea that a citizenry of yeoman farmers would sustain the American democratic experiment, but plenty of non-farmers realized that there was a dollar to be made from it too. Ideally, everyone would profit, or so they argued.

In A New Guide to the West, John Mason Peck wrote in the 1830s about successive waves of settlement on the frontier. Frederick Jackson Turner, in his seminal 1893 essay "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" affirmed this view and quoted Peck at length:

Generally, in all the western settlements, three classes, like the waves of the ocean, have rolled one after the other. First comes the pioneer... He builds his cabin... and occupies till the range is somewhat subdued... till the neighbors crowd around... and he lacks elbow room. The preemption law enables him to dispose of his cabin and cornfield to the next class of emigrants... The next class of emigrants purchase the lands, add field to field, clear out the roads... Another wave rolls on. The men of capital and enterprise come. The settler is ready to sell out and take the advantage of the rise in property, push farther into the interior and become, himself, a man of capital and enterprise in turn. The small village rises to a spacious town or city... Thus wave after wave is rolling westward; the real Eldorado is still farther on.

Peck and Turner depict a rather frictionless process of developing land, so it's important to note that this is a bit idealized. But this is the type of thinking that informed land policy, and it helps orient us to the way people were thinking in the last decades of the 1800s leading to the Reclamation Act. Turner quoted this section at a time when the frontier had recently "closed." But as Donald Worster notes in Rivers of Empire, the line of settlement briefly retreated ten years later in the 1900 census. Prior to federal reclamation, Turner and others expressed concern that westward expansion, due to the extreme aridity of the far West, was faltering. For land speculators, this meant that the cheap land they had invested in might not rise in value. Mining was profitable, but those operations were boom-and-bust, leaving ghost towns behind rather than thriving cities. Cattle and sheep ranching had become established by about the 1880s, but that industry required vast stretches of land and resulted in isolated homes. Speculators needed farmers to develop a permanent population in little villages that could grow to become cities--driving up land values and creating markets--and to do that farmers needed irrigation.

In addition to Jeffersonian (or Weberian) ideas about the work of farming leading to a virtuous citizenry, agriculture was an eminently practical means of reproducing a settler capitalist society. People need shelter; we also need food, something to do, and company. A homestead came with a job and something to eat, even if there wasn't much variety in one's diet. The homesteading family unit provided domestic labor. It was a spartan existence, but an efficient one (assuming as well that a particular society has an army of poor people that can fail en masse without upsetting anyone else too much). Historian and anthropologist Patrick Wolfe speaks to the importance of agriculture in the settler colonial project: "Agriculture is a rational means/end calculus that is geared to vouchsafing its own reproduction, generating capital that projects into a future where it repeats itself... Agriculture supports a larger population than non-sedentary modes of production... The inequities, contradictions and pogroms of metropolitan society ensure a recurrent supply of fresh immigrants--especially... from among the landless. In this way, individual motivations dovetail with the global market's imperative for expansion. Through its ceaseless expansion, agriculture (including, for this purpose, commercial pastoralism) progressively eats into Indigenous territory, a primitive accumulation that turns native flora and fauna into a dwindling resource and curtails the reproduction of Indigenous modes of production."

The irrigation movement of the 1890s represented a new wave of boosterism, and the interests of those involved were more material than cultural, despite their rhetoric. Speculators and professionals wanted federal investment in irrigation for their own sake, but their arguments tended to stress the importance of national and civilizational achievement and the development of democracy on the frontier (similar to Frederick Jackson Turner's argument). The Conquest of Arid America, by one of the founders of the irrigation movement, William Ellsworth Smythe, took that sort of rhetoric to new heights and talked about irrigation as a kind of religious rite.

Farmers and farming were central to this vision, though the actual people doing the hard work were largely instrumentalized. Farmers were willing to accept that fact so long as they got something out of it. The Massachusetts-born Smythe had little in common with, say, a Wyoming farmer, but the promise of new water was not something that Western homesteaders were going to turn down. Exploitation of land in the West happened in the shape of an inverted pyramid. Individuals with wealth stood to benefit the most, but the pyramid extended nearly to the bottom of white society. As long as one was able to move up to the next tier, it hardly mattered how much the people at the top were making off with. While the safety valve effect did not materialize like many had hoped in the early 1800s, there is something to be said for how many people imagined the frontier of the 1830s and '40s through the lens of class conflict and how little of that framework followed homesteaders into the Mountain West. ("Homesteaders" and "Mountain West" are the key words here. Class war here took place in mining towns, and Populist farmers kept up the struggle in the Midwest and the South in the late 1800s.)

Among the motivations for promoting federal reclamation, the production of food and fiber was very low on the list. In fact, the US Department of Agriculture and the National Grange, a farming organization, opposed the 1902 Reclamation Act out of fear that promoting agriculture in the West would result in too much food, thus driving down food prices. It was a valid concern, as plummeting wheat prices contributed to a severe depression in the 1890s.

Here in Utah, Anglo agriculture began as a means of communal self-sufficiency. In order to keep themselves isolated, the Mormons of Utah Territory tried to avoid integration into national markets. This lasted until about the 1890s, when the territory began to "americanize" on its way to statehood in 1896. Farmers who grew staple crops began growing cash crops for export. Locals are likely familiar with the summer festivals that celebrate the harvests of fruits (cash crops) that farmers still grow: Strawberry Days in Pleasant Grove, Peach Days in Brigham City, and so on. (Don't sleep on Onion Days in Payson.) Sugar beets were an important cash crop for Utah farmers in the early twentieth century until overseas cane sugar undercut their prices; part of Utah Senator Reed Smoot's motivation behind the infamous Smoot Hawley Tariff Act was to help protect the state's sugar beet farmers.

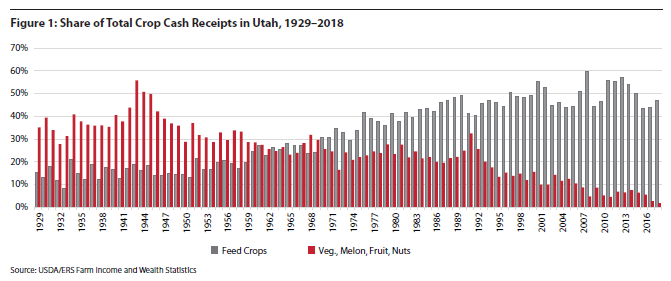

But the real money has been in livestock for at least a century. "Since 1929, about three-quarters of Utah farms' cash receipts, on average, have come from animals and animal products, primarily cattle and hogs," according to economists at the University of Utah. Feed crops to support livestock overtook vegetables, melons, fruits, and nuts as a share of the state's crops in the 1960s and now represent nearly all of the state's cash receipts from crops.

Again, the rise of Western cattle has much to do with land. The West, with its sparse natural forage, is not an efficient place to raise cattle, in terms of yield. But it is efficient in the sense that there are large stretches of public land where animals eat free (minus nominal public lands grazing fees, after the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934) for about eight months out of the year. (Even for privately owned farmland, almost 80% is pasture or rangeland, underscoring the importance of cattle to Utah agriculture.) Consider this: the LDS Church owns a herd of 44,000 beef cattle. Despite the church's longstanding ties to the Mountain West, it grazes those cattle on pasture that it owns in central Florida. If one is trying to maximize investment, it makes better sense to graze cattle on abundant grasses in the Southeast. Despite the importance of ranching to the region, Utah has fewer heads of cattle than North Carolina and about half as many as Alabama.

Similarly, alfalfa is important as an adaptation to place, not necessarily as an efficient crop. Wisconsin in some years is the most valuable producer of alfalfa in the country, though it is only the state's third most important crop. Alfalfa is the top crop for Utah, as it is for Idaho, Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Oregon. But aside from Idaho and Arizona, these states are not even in the top 10 most valuable alfalfa producers.

The economics get even more interesting when looking beyond the aggregate. Drilling down reveals that most Utah farmers are not making that much money from their crops. The USDA classifies a "small farm" as one that makes less than $350,000 per year. About 90% of Utah farms fall into this category; only 3% of Utah farms make $500,000 or more. Furthermore, about two thirds of all Utah farmers report a net loss, and the average loss per farm is about $20,000. Considering that more than half of farmers make less than $5,000 in cash receipts, it is easy to imagine that capital investments or other expenses push farmers into the red, even accounting for the probability that farmers are overreporting losses. To be clear, this is an overall picture of all farms, though again hay and pasture are the top crops in Utah.

About forty percent of Utah's farms grow alfalfa hay, though small farms are more likely than big farms to grow it. On farms smaller than 15 acres, about 47% grow alfalfa. For all farms smaller than 50 acres, about 73% of farms grow alfalfa, according to the 2022 USDA agricultural census. Utah also has a rather high number of farmers whose primary occupation is something other than farming: 69% as of 2022. For lifestyle or retirement farms, alfalfa appears to be the crop of choice.

Alfalfa requires quite a bit of water, which makes it less than ideal for arid and semi-arid environments. But it has other qualities that make it well-suited for the region. It's a perennial and a legume, meaning that it doesn't require yearly replanting and fixes nitrogen in the soil. Farmers can take up to ten cuttings in a good year, which means that if there isn't enough water, there is little loss in taking fewer cuttings. The relatively low value of alfalfa also contributes to the low opportunity cost in letting it dry up. Water writer John Fleck argues that this flexibility actually contributes to the resiliency of water systems in the West.

If we consider the shift in agriculture towards alfalfa in the broader context of urbanization in Utah, things look a bit different. For starters, the best farmland in the state -- the lands that early settlers gravitated to -- is now under concrete. Northern Utah County, for example, used to be full of orchards. As the county urbanized, catalyzed during World War II with the building of Geneva Steel to supply the military, orchards became subdivisions. There are still "secondary water" systems in Salt Lake City, not far from downtown, where irrigation water runs through the gutters of residential neighborhoods. Think of John Mason Peck's successive waves of settlement: farming villages became cities, and farmers pushed out into more marginal land where valuable fruits and vegetables could not grow as well. Additionally, building reservoirs inundates farmland along fertile river bottoms; storage is created at the expense of fertile soil.

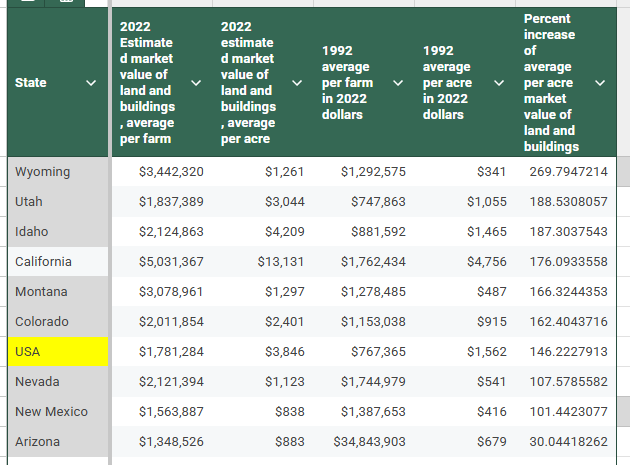

Then there is the matter of finances. Again, most Utah farms report a net loss--the ratio here is pretty high relative to the rest of the country, but the majority of farms nationwide report net losses. The USDA has found that accounting for the increased value of a national average of farmland helps make up for the difference: “Farmland values, which have increased nearly every year between 1990 and 2015, … boosted the returns for these farm operators by an average of $22,661 across all farms in 2015.” In Utah, the average value of land and buildings on farms per acre tripled between 1992 and 2022, from $1,117 to $3,405 (adjusted to 2024 dollars. See 2022 Utah Ag Census).

Now we have a better picture of the median farmer in Utah: someone who works a piece of land they own, without hired help, growing alfalfa for sale or for their own animals, and going to work somewhere off the farm. The median farm size in Utah is 22 acres. The alfalfa itself is not worth all that much to them, but in order to retain their water rights, they need to grow something (use it or lose it). Losing the water rights associated with their property would reduce its value. Alfalfa is a good fit for a lazy farmer, and there are plenty of cows to feed. In fact, seen this way, the inefficiency of cattle is an advantage here. Beef cattle eat up to 25 pounds of feed for every edible pound they produce, a much greater ratio than other livestock. There is little chance of an oversupply of alfalfa from lifestyle farms for this reason, since it would take so much to drive costs down--and in that case beef and dairy operations might just buy more heads of cattle, stabilizing the cost of hay. In fact, increasing dairy production was the response of Idaho farmers to a glut of cash crop alfalfa in the late 1910s, according to Mark Fiege in Irrigated Eden. In 1924, an irrigation official reported, "We have got ten thousand cows and are milking our way out" of the surplus. Fiege writes, "From 1919 to 1924, milk production expanded by 50 percent."

It is true that Utah exports a decent chunk of its alfalfa: about 15% by weight. The region's history with the crop means that Western farmers produce some of the highest quality alfalfa, so specialty buyers source alfalfa from Utah and the Mountain West. This is why the amount of alfalfa exported by value is about 29%. Beef is a similar story; you are not eating pasture-raised Montana beef in your $1.29 McDonald's cheeseburger. Like many others, I am not a big fan of exporting the region's limited water in the form of alfalfa or beef, though my guess (which could be incorrect) is that buyers who pay a premium for these products could absorb a price increase (tariffs? increased water costs?) without moderating their demand all that much.

As for the lifestyle and retirement farms, because making money from growing hay isn't the point, I find little reason to believe that they could be motivated to install costly drip irrigation to improve efficiency. But on the other hand, recent changes to Utah law that allow farmers to let their shares of water go downstream to Great Salt Lake may be impactful for these farms. The big question then is what will keep their land from drying up and being invaded by weeds.

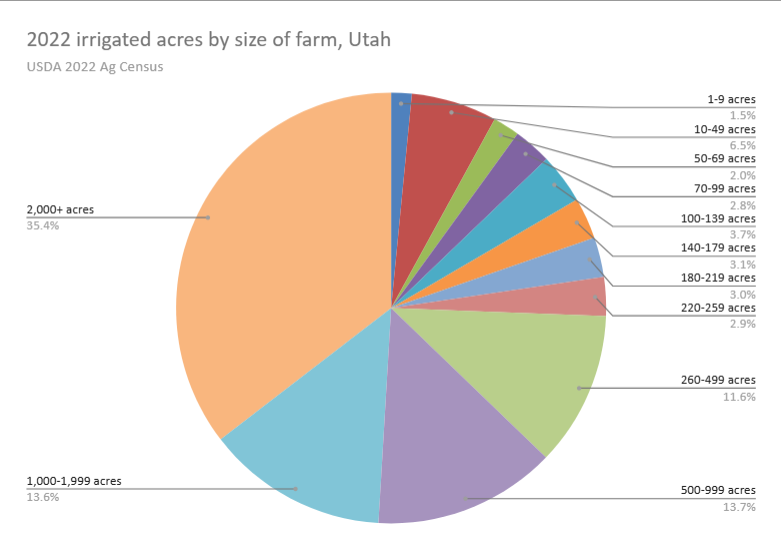

To be fair, the majority of irrigated acres are concentrated on the relatively few large farms in the state. So while farms under 50 acres make up almost two-thirds of all farms, about 75% of all irrigated acres are on farms greater than 260 acres. This may make changes to water policy a bit more manageable, though it is still important to understand the implications that changes in crop or animal production would have on rural communities. (Chart below by author)

The point of all this is, yes, agriculture needs to do something differently. There's no serious debate suggesting otherwise. It consumes such a large chunk of water that there is just not enough for everyone to be able to do whatever they want. At the same time, it is a big mistake to fail to consider agriculture as part of a bigger picture, since no one sector exists independent of the others.

(Note: This post was updated 9/9/24 to include a detail from Irrigated Eden.)

(Note: Updating again 2/6/2025. I wanted to include the following data in the image below to avoid presenting a misleading picture. I compared the rates in the increase of the average acre of farmland and buildings in Western states, finding that a number of them outpaced the national average. The value of farmland and buildings in Wyoming, Utah, and Idaho grew faster than California -- which is pretty remarkable considering the dominance of low value forage crops in these states, compared to the more valuable fruits and vegetables in California. But one expect that this would hold true for Nevada, New Mexico, and Arizona as well. Not sure what is happening with Arizona.)

References:

Frederick Jackson Turner, ["The Significance of the Frontier in American History,"](https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/historical-archives/the-significance-of-the-frontier-in-american-history-(1893)) *Annual Report of the American Historical Association* (1893)

Donald J. Pisani, Water and American Government: The Reclamation Bureau, National Water Policy, and the West, 1902-1935, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002)

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 no 4 (2006): 387–409.

Charles S. Peterson and Brian Q. Cannon, *The Awkward State of Utah : Coming of Age in the Nation, 1896-1945* (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and The University of Utah Press, 2015).

Daniel L. Prager, Sarah Tulman, and Ron Durst, “Economic Returns to Farming for US Farm Households” (US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, August 2018).

Mark Fiege, Irrigated Eden: The Making of an Agricultural Landscape in the American West (Seattle: University of Washington, 1999).

**Read more:**

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century