The Safety Valve

There are some narratives about the US West that have taken on a life of their own, independent of whether they are true. The West is a resource colony for the East. The West is running out of water. And the topic of this entry: the West is a safety valve for the sociopolitical pressures that build up in the rest of the nation.

The "safety valve" articulation manifested in the early 1800s, after the invention of the steam engine. But some version of the idea was around about a half century prior as the founding generation laid the plans for the new republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that opening the frontier would prevent social unrest in cities, as workers otherwise dependent on wage labor could seek their own fortunes rather than stewing in their discontent. For political theorists of Jefferson's day, civilization was a fragile thing that revolutions could destroy if the proper precautions were not taken.

The founding of the Virginia colonies themselves may be the earliest implementation of the safety valve principle. With England facing a population boom and a growing number of urban poor by about the mid-sixteenth century, property owners and aristocrats feared an "imminent collapse into violent anarchy," according to historian Alan Taylor. Promoters of North American colonization used this as an argument in their favor: colonies would allow for the export of London's poor, nuisances who occupied themselves with crime. In fact, sending thousands of poor men, women, and children abroad kept the Jamestown colony afloat amid disastrous mortality rates in its first couple of decades.

The reality of the safety valve phenomenon was arguable at best, though there are issues which the availability of plentiful land (once violently cleared of Indigenous peoples) made much more easily resolved. For the founding generation, an abundance of new settlements helped lead to the abolition of primogeniture, the English-based law requiring that a landowner leave the entirety of his estate to the eldest son, for example.

By the 1830s, the opening of the frontier was supposed to benefit workers in Eastern cities, since any of the unemployed could establish a homestead on the plains while workers who stayed behind saw their bargaining position enhanced. This at least was the theory. As the influential newspaper publisher Horace Greeley wrote, "The public lands are the great regulator of the relations of Labor and Capital, the safety valve of our industrial and social engine." Accordingly, northern industrialists opposed homesteading policy because they feared their workforce might flee to claim a piece of property of their own.

With Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase and Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act, the architecture of a white man's democracy was in place. But class politics became subsumed into debates over slavery by the 1850s. The Free Soil Party, which would help launch the Republican Party in 1854, argued that homesteading would prevent the spread of slavery into the West as smallholding farmers were allowed to put down roots. A "free land" policy became a priority for President Lincoln during the Civil War; the president hoped that offering homesteads to poor Southern white men would help chip away at support for the Confederacy. With the Southern states having seceded, the US Congress was able to pass the Homestead Act in 1862 after a decade of trying to pass similar legislation.

The West was unable to properly serve as a vent for the pressures of sectional conflict. The South seceded, after all, and the country fought a civil war. But that hardly stopped people from hoping. Part of the inability of the safety valve to work as imagined was the fact that people holding contradictory positions all saw it leading to their preferred outcomes. Some proponents of slavery hoped that the opening of new territory would keep the institution alive. (And some abolitionists argued against "safety valve" measures, including the colonization of African land for the deportation of free Black people, because they wanted the metaphorical boiler to break down entirely.) As historian Greg Grandin observes, "What matters is that invocation of a 'safety valve' allowed individuals to simultaneously answer and evade a question. Inherent in the metaphor is the recognition of the profundity of the problem that Jacksonian democracy represented and resignation that the problem wouldn't be solved within the existing terms of social relations and political power." Over time, the promise of venting difficult political problems turned into a hope that conditions might be different, more pliable, somewhere else out on the frontier. The West became less of a safety valve and more of a blank canvas.

The safety valve effect, after all, was minimal. "The Homestead Act failed to help the Eastern urban laborer as woefully as it failed to help the farmer in the West," according to Henry Nash Smith in his classic book Virgin Land. Even with half a continent on offer, not enough settlers headed for the frontier to make a difference in the East. Nor were they all poor laborers as intended. In the first decade after the Homestead Act was passed, more land was purchased outright than claimed for free. Even with the offer of free land, moving and establishing a farm was prohibitively expensive for many workers. Established Eastern farmers and others with a little bit of savings or property were better able to take advantage of cheap, plentiful land.

There is another important aspect to westward migration. It required mobility. To find one's desired society, one had to physically move in search of it. As Richard Slotkin wrote, tracing the history of the frontier back to the Atlantic Ocean, "Emigration was a necessary prelude to any truly American story... The completed American was... one who remade his fortune and his character by an emigration, a setting forth for newer and richer lands."

Or, someone else needed to go searching for their own fortune, easing the crowding for those who stayed in the East. By the time the irrigation movement organized in the 1890s, their slogan, "Put the landless man on the manless land" was as much a promise to nudge immigrants out of Eastern cities as it was a call for opportunities for yeoman farmers. Horace Greeley's slogan from earlier in the century, "Go west, young man" became, over time, a euphemistic way to tell someone to fuck off. Still, the safety valve concept had purchase, particularly as it was "supposed to offer the men of property and wealth a means of maintaining social peace," according to historian Donald Worster. As Senator Thomas Patterson put it, the 1902 Reclamation Act would be "better than a standing army" in its ability to quell the "danger of great social disturbances in the great cities."

Again, because the effect was muted, the safety valve was an ambiguous boon to the wealthy. But the series of legislation that helped open up the far West for the development of its resources was much less ambiguous. Where Northeastern capital had opposed homesteading earlier in the century, some companies began to see how "free land" could work to their advantage. In particular, railroad companies managed to acquire nearly 200 million acres from the federal government, and those companies fraudulently availed themselves of extra land through the Homestead Act when possible. All told, homesteaders ended up with a quarter or a third of Western public land that was claimed by private owners. The wealthy also quickly dominated the mining industry. The plucky prospector, who serves as the popular image of gold and silver mining, was quickly superseded. The railroads themselves bought and operated a number of coal mines, using the product to fuel their trains as well as to sell. And by building a transportation infrastructure, the railroads could move goods across regions. The promise of new markets in the West appealed to those with money to invest. The storehouse of the West promised a great number of resources, and burgeoning Western populations needed to be linked up to the rest of the country in its buying and selling.

We like to think that the West was settled by a legion of Jeffersonian farmers, though it may be more accurate to think of homesteaders being pulled westward in capital's wake. While it is true that the Homestead Act and its subsequent iterations gave an enormously valuable opportunity to poor white men at the expense of Indigenous peoples, policymakers gave little thought to the success of any particular homesteader. By the time the Reclamation Service was established in 1902 to help extend the bounds of the frontier, creating a farm in the high desert was a sink or swim proposition. The Service in its early years refused to test soils, leading to a number of irrigated farms failing because of alkali. Reclamation leaders tended to blame farmers for these types of failures.

A large part of the purpose of building dams is to control and regulate the flow of water. Many dams across the West are built simply for flood control. Because rivers in the West are fed by snowpack accumulated over the winter, they run excessively high in the spring and slow to a trickly by the end of summer. Dams smoothe out that natural curve. They rationalize water, making it conform to the needs of human industry. In contemporary times, this comes with a steep tax--about ten percent of the water in the Colorado River Basin evaporates out of Lakes Powell and Mead every year. Similarly to water, as humans became more mobile, the flows of labor cried out to be rationalized and channeled according to the needs of capital investment. This is true, to an extent, for the successive waves of white farmers who tried to gain a foothold in the arid West. It is truer in the case of the Irish and especially Chinese wage laborers who built the railroads. The railroads, writes Malcolm Harris, "needed people who were estranged from the land." Racial differentiation and segregation between white and non-white workers, encouraged by the region's more powerful white labor organizations, helped to create a dual labor system which kept non-white workers cheap and mobile. With the transcontinental railroad completed, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and anti-Chinese lynchings placed a limit on the Chinese population in the West, something which pleased the Knights of Labor. Those Chinese people who stayed in Western towns found themselves confined to doing laundry or cooking lest they compete with white workers. California's Alien Land Law of 1913 prevented Asian people (mostly Japanese) from owning land -- resulting in successive waves of migrant Asian labor -- Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino -- who came for opportunities on farms and then fled from pogroms. Something similar could be said of cowboys, or "cow herds" or "cow punchers," a large percentage of whom were Black or Latino. Mexican-Americans and Chicanos, many of whom have roots in lands that the US annexed from Mexico since 1848, provided hard manual labor only to have the federal government import Mexican workers through the Bracero program of the 1940s and '50s, partly an attempt to keep farmworkers from unionizing. To keep them from staying. The Western economy channeled flows of different types of labor to where they were needed, complete with valves that could be closed and racial barriers to keep the streams moving at different paces.

Robert O. Self writes, "Following the war, national industry decentralized and patterns of national capital investment and human migration and immigration shifted to the West... Federal tax policy and public works expenditures, particularly on highways and airports, facilitated industrial dispersion to the West. Local and state governments also encouraged capital mobility by recruiting firms with advertisements about their comparative advantages such as low taxes and low wages. These dramatic movements of people and capital to and through the region constituted far more than a brief 'gold rush.' Rather, they reprsented new national trends in which western cities would sustain their place as magnets of population growth and investment." Labor historians are familiar with a phenomenon known as deindustrialization. Having created the industrial backbone of the country in Eastern cities -- Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Buffalo -- in the first half of the twentieth century, corporations proceeded to dismantle it in the last half. One significant motivation was to break the power of unions in those cities. The automakers, for example, built new facilities outside of urban centers such as Detroit, spreading out parts of the manufacturing process to Dearborn or Hamtramck. White executives and managers fled the cities for the corresponding suburbs. In some cases, heavy industry relocated operations to the "Sunbelt" that stretched across a southern swath of the country. The Southeast had long been resistant to organized labor, and the Southwest had not quite given unions the chance to become established. I've gone a little far afield here, since deindustrialization was not strictly a Western phenomenon. But the West saw a great deal of capital investment during and after World War II, from the private sector as well as the Department of Defense. As capital moved to fill in the region, it needed to attract labor. In order for that to happen, labor needed to be continue to be mobile.

Seen this way, the Bureau of Reclamation after World War II accomplished a number of objectives related to the goal of creating a place for capital to flee. During its heyday, the Bureau shifted to multi-purpose projects which largely benefited cities in addition to farms. Hydropower from Reclamation dams met the increased electrical demand from industry as well as home air conditioners (subsidized by tax breaks at one point in the last half of the twentieth century). Abundant water meant that suburban homes could have lawns of Kentucky bluegrass in the desert, and nearby reservoirs provided middle class families with something to do on the weekends. People could move in and out of Salt Lake City or Phoenix or Las Vegas as if they were any other city in the country, with the inhospitality of the high desert presenting an inconvenience at worst.

To an extent, this runs counter to the whole purpose of irrigating the West. Western politicians and land speculators by the end of the nineteenth century were dissatisfied with the ability of ranching and mining to populate the region. Ranching was too spread out, and mining was too transient. Farming would create a permanent population. But the goal was for those farming villages to develop into cities--the farmers themselves would have to sell and move if they wanted to continue farming (not that the farmers were necessarily averse to that scenario). It is hardly unique to the West that individuals, families, and communities must answer the demands of capital, but the necessity of staying mobile may be more deeply written into the region's fiber than anywhere else in the country.

The West, in this sense, is an idea as well as a geography. Elon Musk, dissatisfied with California's labor and environmental regulations, recently moved the headquarters of Tesla east to Texas, a more "business friendly" state. Yet even that was not enough, as Musk has attempted to sidestep environmental regulations and city taxes by withdrawing his factory from the city of Austin's purview. The Western conservatism that has taken root in Texas and the Mountain West believes in limited government---except for the government investment that manages the region's resources and infrastructure and helps attract businesses and residents. That is a topic for another essay. Suffice it to say that in-migration has caused the West to be the fastest growing region in the country since the mid-twentieth century.

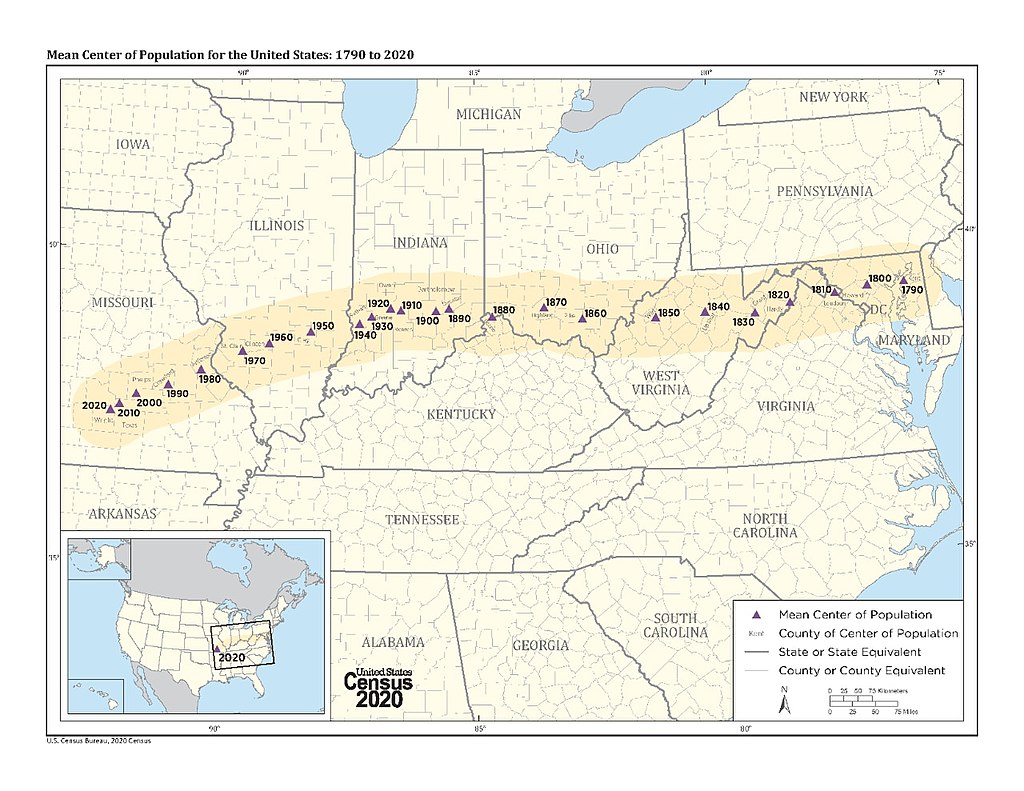

|

|---|

| US Mean Center of Population over time |

Here on the Wasatch Front, the Silicon Slopes initiative attracts tech companies and their workers, promising all the amenities of (government managed) natural areas as well as cheaper labor and lenient regulations. In addition to Silicon Valley, there are a number of burgeoning tech centers across the West, typically supported by local and state incentives: Silicon Coast, Silicon Desert, Silicon Forest, Silicon Hills, Silicon Mountain, Silicon Prairie, Silicon Shore, and Silicon Spuds. The incentives for relocating used to include a lower cost of living, though by now those of us who live on the Wasatch Front are being priced out of housing for the sake of "the economy."

The goal of controlling the natural flows of Western water and diverting them to where humans want and need them has long run parallel to the goal of developing labor markets. The tendency of humans to put down roots, to make friends and communities, to develop attachments to a place and to each other can be disrupted like wild rivers, and like water our labor can be stored and diverted and channeled to where it is desired. For those of us who work for a living, the opportunity to be mobile that the West provides can also come with an obligation to stay that way.

(For an exploration of who stays and who leaves in the face of ecological hazards, specifically related to Great Salt Lake, check out the Stay Salty: Lakefacing Stories podcast here.)

(Note: This post was updated 1/16/2025 with an additional quote and source about federal investment in the west and labor mobility.)

References:

Alan Taylor, American Colonies (New York: Viking, 2001)

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995)

Greg Grandin, The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019)

Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950)

Richard Slotkin, The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800-1890 (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1985).

Richard Edwards, Jacob K. Friefeld, and Rebecca S. Wingo, Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017).

Richard White, "It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own": A History of the American West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991)

Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985)

Donald Pisani, Water and American Government: The Reclamation Bureau, National Water Policy, and the West, 1902-1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002)

Ryan Dearinger, The Filth of Progress: Immigrants, Americans, and the Building of Canals and Railroads in the West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015)

Malcolm Harris, Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2023)

Rick Baldoz, The Third Asiatic Invasion: Empire and Migration in Filipino America, 1898-1946 (New York: New York University Press, 2011)

Robert O. Self, "City Lights: Urban History of the West," in A Companion to the American West, ed. William Deverell (Malden Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2004)

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996)

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

[Note: this post was updated 10/27/2024]