The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis

The first irrigation project on federal land began in 1867. It was authorized through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) for the Colorado River Indian Reservation. It was never completed. Since then, the BIA has begun work on 125 irrigation projects but has not completed any of them.

Given that the project was in an entirely different major watershed, what does this have to do with Great Salt Lake?

I've decided to start this series in this way because it will help to draw out two important points: agriculture was culturally and ideologically very, very important for nineteenth-century America, and agriculture was very, very difficult in the Interior West. Concerning the second point, there is a simple explanation for why the Colorado River Indian Irrigation Project wasn't completed: the project was poorly planned, went over budget, and ran out of money. The more intriguing question is why settlers invested so much time, money, and effort into the irrigation works that make agriculture viable. The Great Basin runs from Utah to Nevada--the two driest states in the country--and includes the Mojave Desert in California. There is not enough rainfall in the Interior West to support farming, and high elevations mean a shorter growing season. Much of the land is alkaline, meaning that crops will not grow with any amount of water. There are not very many compelling reasons to start an agriculture industry in such a place. Yet the Bureau of Reclamation has built nearly 350 dams in the West, and the Army Corps of Engineers has built over 200 in the region as well. The total number of dams in the West totals an estimated 30,000 (though, to be fair, dams are not built solely for crop irrigation).

|

|---|

| Hydrological map of the Great Basin |

The reason for all this dam building is fairly simple. Farming, for centuries, has been very important as a way of turning land into property. And without irrigation, there is no farming in the West.

The first British settlers in North America reasoned that the land was theirs to claim because the Algonquian peoples had not "improved" it--that is, they did not farm by clearing forests and tilling the land. When blessing the Jamestown colony in 1609, a reverend asked, "The first objection is, by what right or warrant we can enter into the land of these Savages, take away their rightful inheritance from them, and plant ourselves in their places, being unwronged or unprovoked by them." His answer was that the Indigenous people were not properly using it. Later, the Puritans of the Plymouth Colony would use the same logic.

However, the Indigenous North Americans were farmers. They planted and cultivated maize, squash, beans, and other crops. Additionally, their forest management practices encouraged the growth of nut trees and healthy populations of wild game. These carefully tended forests, much different from the overgrown wilds of England, so impressed the Puritans that they compared them to the Garden of Eden. Yet the settlers were unable to recognize the work and knowledge that went into cultivating the forests in this way--and they were unwilling to abandon the justification that the Indians were living in a "state of nature." Because of this, they imagined the "New World" as virginal land, ready to be cleared and planted. As a way of "civilizing" the Indigenous peoples--teaching them Christianity and European-style farming--the Puritans established Praying Towns. One of the important distinctions in the different modes of farming was that the Native Americans held their goods in common, while the English settlers' mode of production was one based on private property.

Later in the 17th century, political theorist John Locke would articulate a version of property in line with what the Puritans had rationalized. A person who applied their labor to some raw material--land, in particular--had a natural right to claim it as their property. Plowing a field, then, made the land one's own in a way that transcended law. Locke's Second Treatise was very influential in Angloamerican jurisprudence and set the stage for the westward expansion that would accelerate a century later.

Land-hungry settlers hardly needed additional motivation for pushing west of the Appalachian Mountains in the 18th century, but the founding generation, most notably Thomas Jefferson, articulated an important political role for farmers. Jefferson, in line with the political philosophy of the day, believed that societal progress was cyclical. Farming allowed for sufficient population density that civilization could develop, but civilization eventually tended to break down and revert to a primitive state. He imagined that yeoman farmers and the democratic values that they cultivated could create a republic that would be more resilient than one composed of idle urbanites. But this required a constant supply of land.

Federal land policy, following the War for Independence, began to embrace westward expansion. The government instituted a rectilinear survey to help turn western plots of land into property. Eastern political maps tended to follow natural boundaries and land features. Western states and counties, which subdivided into a checkerboard of plats, became large blocks of land which only make sense in the abstract, on a map. When Utah was carved up into its current boxy shape, the straight lines on the map cut across parts of two major watersheds.

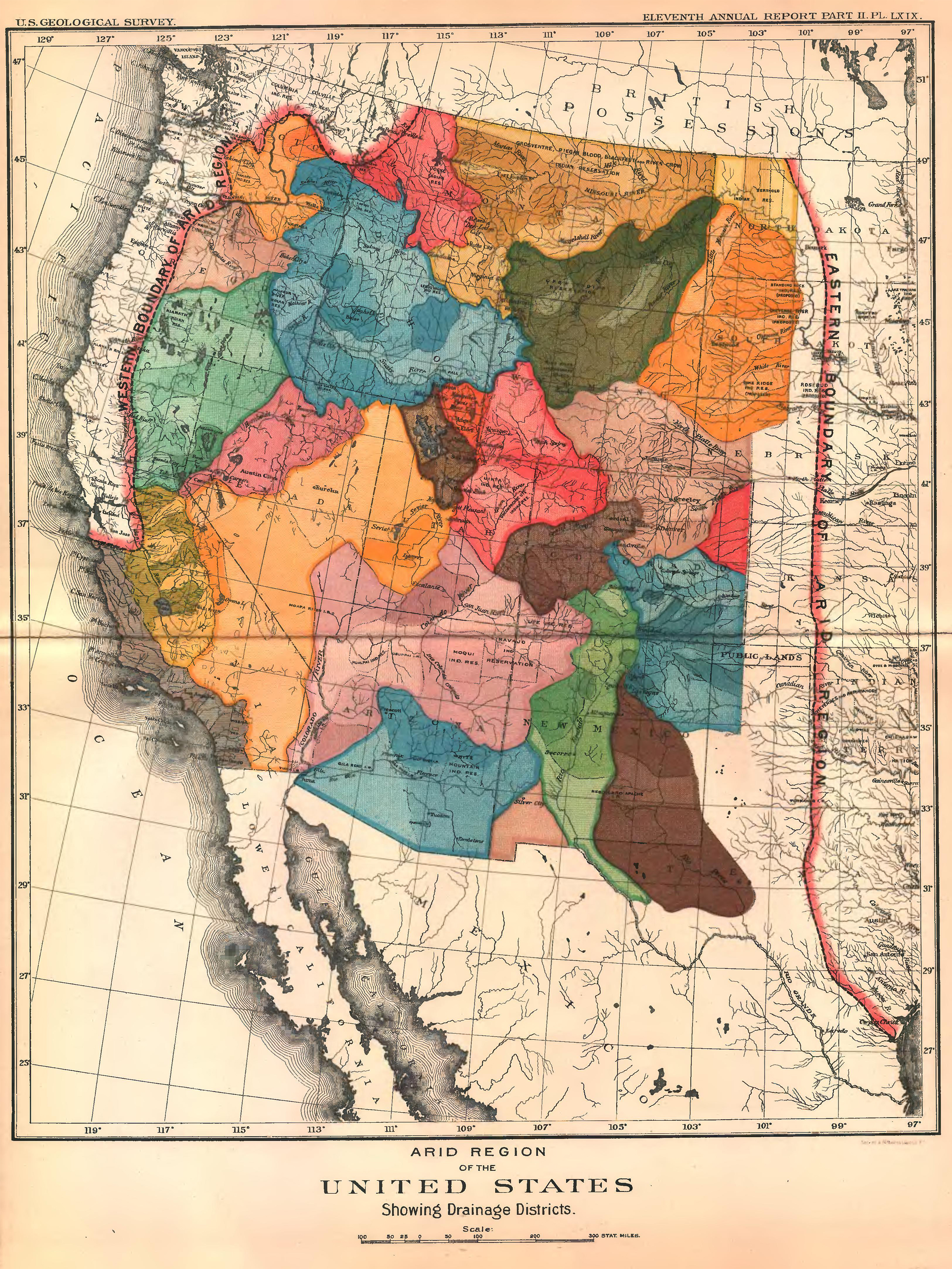

Notable explorer and scientist John Wesley Powell proposed an alternative in 1878. Water was so important to settlement and in such short supply, he argued, that political districts should be based on watersheds. To do otherwise would invite unnecessary strife. Despite the extensive research that went into Powell's report and despite his renown--he would soon go on to become the director of the US Geological Survey--Congress rejected his proposal. The idea that settlement in the Far West might be constrained by a lack of water contradicted Manifest Destiny--its expression in the 1870s was the pseudoscientific belief that rain would follow the plow, that tilling and planting created a wetter climate. Additionally, Western "boosters"--land speculators who relentlessly promoted settlement--had considerable influence in setting land policy. Policymakers considered the aridity of the West to be a minor hurdle that could be overcome one way or another.

|

|---|

| Powell's proposed map |

Let's jump back in time slightly and return to the Colorado River Indian Irrigation Project. As the federal government began establishing reservations for Native Americans in the West, Indian policy began to shift toward using agriculture as a way of assimilating Natives into Anglo society. CRIIP was an attempt to help the Colorado River Indian Tribe--a Tribe made up of Mohave, Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Diné peoples--establish farms with an eye toward "civilizing" them. The idea was as old as the Praying Towns of New England. Mormon settlers also set up Indian Farms in Utah Territory in the 1850s, but with little success.

This explains the motivation behind building irrigation works for Western Indians, but what explains the lack of commitment to finishing them? Again, the simple explanation is that irrigation proved to be much more difficult than hubristic federal officials anticipated. Beyond that, even the self-styled "Friends of the Indians" held deeply ambivalent views about their goal of helping Indigenous people to establish a permanent presence on the land. 19th century scientists and intellectuals held it as a matter of fact that "savage" and "barbarous" peoples were destined to disappear, one way or another, when competing with white civilization. The anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan articulated this progressive view of human society in his 1877 work Ancient Society--which connected these different stages to modes of food production. Morgan was a mentor to John Wesley Powell, who, despite his dealings with Utah's Paiutes during his Colorado River expeditions, believed that Native Americans were "savages" who needed to abandon their traditional economies. He opined, "The sooner this country is entered by white people and the game destroyed so that the Indians will be compelled to gain a subsistence by some other means than hunting, the better it will be for them." Even commissioners of the Bureau of Indian Affairs around the turn of the century expressed similar ideas. Francis K. Leupp wrote of the Indians, "Perhaps, in the course of merging this hardly used race into our body politic, many individuals, unable to keep up the pace, may fall by the wayside and be trodden underfoot. Deeply as we deplore this possibility, we must not let it blind us to our duty to the race as a whole." This social Darwinian approach allowed for failure as an unfortunate but perhaps necessary outcome of social progress.

In 1887, the Dawes Act initiated the allotment era. Indian reservations were partitioned into allotments for each household or adult male under the belief that privately held farm plots would better assimilate Indians than collectively held reservation land. In the 1890s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs renewed its efforts to irrigate Indian land. However, just as allotment put "surplus" lands up for auction for settlers and thus dispossessed Native Americans of much additional land, Indian irrigation projects actually made Native land more desirable to settlers and hastened dispossession. When the Reclamation Service was established in 1902, Indian irrigation projects through the BIA, for a time, actually served as a way for Reclamation to balance its budgets. These types of abuse created an additional problem as the BIA struggled to complete irrigation projects. Federal Western irrigation projects, then, proceeded along two parallel tracks. Indian irrigation had a head start of 35 years, yet quickly fell far behind.

Again, what does this all mean for Great Salt Lake? Nineteenth-century land policy treated the Western landscape as a blank slate, ready to be carved up and turned into farmland. This was to the benefit of both settlers and land speculators, though for the national imagination it simply could not be otherwise. If civilization was somehow unable to take wild lands and make them productive, it would not be civilization. Western Native Americans, like any Indigenous peoples, had developed successful adaptations to the environment that included farming, hunting, gathering--and cultural and political structures which reflected and reinforced these economic adaptations. But a recognition that Indians did not merely live in a "state of nature" would implicitly challenge, on some level, the right of settlers to claim Indigenous land. Settlers had an ideological imperative to transform the land--to undermine Indigenous lifeways and demonstrate their supremacy.

The nineteenth century is still with us. The legal doctrine governing water in the West, prior appropriation, was developed in the 1800s and privileges senior claims. Many water rights in Utah go back to the 1800s. But beyond that, the fundamental assumptions and premises that encouraged Western settlement continue to impact the way that Utah thinks about the landscape. These have changed shape through the twentieth century, but they have not entirely faded away. In subsequent posts, I will explore this idea and attempt to demonstrate the contemporary impacts on Great Salt Lake and water throughout the West.

References:

Monique C. Shay, "Promises of a Viable Homeland, Reality of Selective Reclamation: A Study of the Relationship Between the Winters Doctrine and Federal Water Development in the Western United States," Ecology Law Quarterly 19 (1992): 547-590. See also Donald J. Pisani, "Irrigation, Water Rights, and the Betrayal of Indian Allotment," Environmental Review 10 no 3 (Autumn, 1986): 157-176; Andrew Curley, "Unsettling Indian Water Settlements: The Little Colorado River, the San Juan River, and Colonial Enclosures," Antipode 0 no 0 (2019): 1-19; Kaylee Ann Newell, "Federal Water Projects, Native Americans and Environmental Justice: The Bureau of Reclamation's History of Discrimination," Environs 20 no 2 (June 1997): 40-57; and Ann Caylor, "'A Promise Long Deferred': Federal Reclamation on the Colorado River Indian Reservation," Pacific Historical Review 69 no 2 (May 2000): 193-215.

Alan Taylor, *American Colonies: The Settling of North America* (New York: Viking, 2001).

Robert Nichols, Theft is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020).

David Rich Lewis, Neither Wolf nor Dog: American Indians, Environment, & Agrarian Change, (New York: Oxford, 1994).

Donald J. Pisani, Water and American Government: The Reclamation Bureau, National Water Policy, and the West, 1902-1935, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). See also Pisani, "Irrigation, Water Rights, and the Betrayal of Indian Allotment."

I also recommend checking out this beautiful aerial view of fallowed farmland belonging to the Colorado River Indian Tribes, by Russell Albert Daniels.

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

[Note: This post was updated on 2/14/2024 with an additional quote relevant to the Jamestown Colony.]