Reclamation in the Prophetic Perfect Tense

The prophetic perfect tense is a literary style found in the Bible, where something prophesied is written as if it has already occurred. The tense reinforces the idea that the prophesy is so certain that it might as well already have happened.

One could argue that the history of reclamation in the West has been written this way. "Reclamation" is not a term that is specific to the US West. Broadly speaking, it refers to an action meant to turn a "waste" into productive land. The Army Corps of Engineers's efforts at land alteration in the East, building canals and levees and draining swamps, predate the earliest Western irrigation efforts by several decades. "Federal reclamation," however, in the context of the West, refers to projects primarily built to put water on arid land.

In practice, reclamation is a concept distinct from irrigation. This is clear when looking at the history of Indian irrigation, which (to my knowledge) never refers to such as reclamation. Federal reclamation, and any other state or private irrigation project that can be folded into the larger project of nation-building in the West, had a loftier mission than just growing crops. The purpose was to reclaim land, to recover it from wilderness for civilization. The term suggests that the desert wastes once belonged to humanity, and that it was humanity's destiny to claim them once again.

In the first chapter of the King James Version of Genesis, God tells Adam and Eve, "Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth." There again, in the replenish, is a suggestion that populating all of the earth's wild places is a restoration to some previous, perfect state. In the same verse, God gives them dominion over "every living thing." The Mormons that settled the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 believed very literally in these ideas.

Yet it is striking how closely the views of secular people about the region's destined rejuvenation lined up with that of the Mormons, a very dedicated religious people with a strictly literal reading of the Bible. The secular version is what Henry Nash Smith called the myth of the garden, and it has long been based almost entirely on faith. Lakota theologian Vine Deloria, Jr. observes how religion and secular society bled into one another in the US: "Instead of working toward the Kingdom of God on Earth, history becomes the story of a particular race fulfilling its manifest destiny... A variant of manifest destiny is the propensity to judge a society or civilization by its technology and to see in society's effort to subdue and control nature as the fulfillment of divine intent." Deloria is examining manifest destiny by noting the preoccupation of Anglo-Americans, or Western religion, with time, in contrast with the importance of space to Indigenous North Americans. Osage theologian George Tinker later affirmed this as well: "For Native peoples, space is primary; for immigrant cultures, time is primary." Additionally, Tinker identifies manifest destiny as "quintessentially a temporal doctrine even as it consumed the space of this continent" because space for Anglo-Americans has long meant "room to expand, to grow, or to move around in: these are temporal processes." (For what it's worth, religious scholar Gil Anidjar, in his reading of Edward Said's work, also declares, "Secularism is Christianity.")

Yet understanding manifest destiny (correctly, in my view) as a temporal process is only the beginning of the puzzle. Donald Worster observes that Western history ("almost an oxymoron") is about "a people who had turned their back on time." Westward settlement, in the myth of the garden, "affirmed a doctrine of progress... On the other hand, the West was supposed to offer a place to escape civilization." For Worster, "Logic says that you cannot have it both ways, physics that you cannot go forward and backward in the same moment. Yet the agrarian myth was able to hold both possibilities together because it did not follow the rules of logical discourse; instead, it was a song, a dream, a fantasy that captured all the ambivalence in a people about their past and future."

The West, in this view, is a space outside of space, a time outside of time. It is the eschaton: an escape from the logical limitations of this world. Contemporary Mormon usage of the word "Zion" exhibits this slippage, from a physical place, in the past or future, to an unrealized state of being in time. The Doctrine and Covenants defines Zion as "the pure in heart," which any congregation of LDS church members can theoretically realize wherever they are. But it also refers to the ancient city of Jerusalem, or to the place in Missouri where the faithful will gather right before the Apocalypse. In a light-hearted way, Mormons also refer to Utah (in the present) as Zion.

The Jeffersonian, agrarian view that propelled westward settlement grew out of a time-based view of human society -- but that view was cyclical. For Jefferson and others who were fond of Enlightenment political thought, society progresses toward its apex -- civilization -- before corruption weakens the edifice and causes it to crumble back into primordial anarchy. As American society oriented itself toward the Western frontier -- an expanse of land considered inexhaustible at one point -- the cycle of progress became a line that would trend upward forever. Moreso than anywhere else in the country, the development of the West occurs in the prophetic perfect tense.

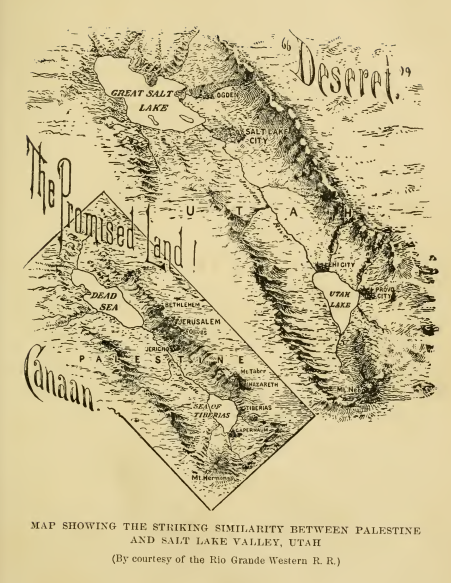

Water, as the key to the West's development, has always been treated by Anglo-Americans as something that would somehow appear when needed. 1873's Timber Culture Act anticipated that planting forests would create a wetter climate. This coincided with "rain follows the plow" pseudoscience. Where John Wesley Powell's 1878 report on the country's arid region cautioned that water was in short supply, the irrigation movement of the 1890s responded to Major Powell's scientific measurements with sheer optimism and nationalistic fervor. William Ellsworth Smythe's 1900 book The Conquest of Arid America refers to "the blessing of aridity" in one chapter and "the miracle of irrigation" in the next: "The glories of the Garden of Eden itself were products of irrigation." An illustration in the book compares "Deseret" with the "Promised Land" of Palestine.

The drafting of the Colorado River Compact in 1922, which is still in force today, assumed an average flow within the river system based on unusually wet years. While the overestimation was due less to magical thinking and more to political pressure and a suspicion that even with over-generous allocations lawsuits would continue through the century, the Compact is a functioning monument to hubristic thinking about the domination of nature. And, no one at the time was looking too keenly into overly optimistic planning for the West. Today, Upper Basin states are still trying to claim water which only exists on paper. Only in the last few years has the mythical garden in westerners' minds started to dry up. It will be some time before we are ready to collectively think about the actual future and not the prophesied one. In 2022, a councilmember in the town of Hurricane, in southwestern Utah's rapidly growing Washington County, expressed reluctance about a conservation ordinance. "I believe the Lord will provide us water," he said. The council passed the ordinance anyway.

**References:**

Vine Deloria, Jr., God is Red: A Native View of Religion (Golden: Fulcrum, 2003).

George Tinker, "Native Americans and the Land: 'The End of Living, and the Beginning of Survival'", Word & World 6 no 1 (1986): 66-74.

Gil Anidjar, "Secularism," Critical Inquiry 33 no 1 (Autumn 2006).

Donald Worster, Under Western Skies: Nature and History in the American West (New York: Oxford, 1992).

John Wesley Powell, Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1878).

William Ellsworth Smythe, The Conquest of Arid America (New York: Harper & Bros., 1900).

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century