Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

At the turn of the twentieth century, the population of Los Angeles had just cleared 100,000. This made it a fair bit larger than Salt Lake County, but the desert metropolis was still merely burgeoning. One of the main constraints on its growth was water.

In 1908, construction began on the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Completed five years later, this canal diverted the Owens River over 200 miles away, almost completely drying up the terminal Owens Lake. A later extension would also lower the level of Mono Lake substantially. The aqueduct ended agriculture in the Owens Valley and dramatically altered the ecology of both lakes. The fine dust left behind as Owens Lake dried posed a health hazard for nearby residents, and the regular dust storms were known as "Keeler fog," named for a town on its shore. Advocates for Great Salt Lake have long drawn parallels to these terminal lakes; the founders of Friends of Great Salt Lake found inspiration in the successful use of the public trust doctrine in protecting Mono Lake. A 1979 lawsuit against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power successfully established that California had a responsibility to preserve the public resource of Mono Lake which overrode Los Angeles's water rights. Advocates for Great Salt Lake continue to investigate a way to use the public trust doctrine in a similar way to protect the lake, but the fact that there is no single entity draining the lake's water sources makes this remedy potentially unviable.

The rapid growth of Los Angeles led to a much more significant event for the entire region. The other Western states in the Colorado River basin feared that California would tap into the river, put its waters to beneficial use, and lay claim to it before the other states would have a chance to do the same. The doctrine of prior appropriation which governs water rights in the West makes it conceivable that all upstream users on the Colorado River would have had to let the water flow right by them if California had allocated it and put it to use. Riparian doctrine, by contrast, allows anyone adjacent to a river to use its river as long as they do not diminish it for downstream users. Prior appropriation allocates water rights based on seniority.

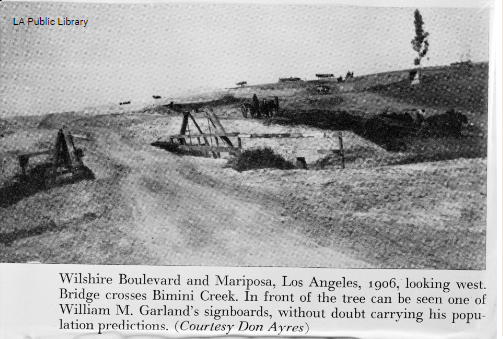

|

|---|

| 1906 photo in what is now Beverly Hills |

|

| 1932 Wilshire Blvd, not far from the photo above. Courtesy LA Public Library |

The origins of prior appropriation lie in the gold fields of the Sierra Nevadas in the late 1840s, though each Western state adopted its own version over the course of the nineteenth century. (California is unique in maintaining an awkward and complicated combination of prior appropriation and riparian rights.) Water in the West was in such short supply that diversions of rivers and streams could and did dry up entire waterways, so riparian rights were not optimal. Nor was it ideal for someone to be able to claim a portion of the water and squat on it, unused, while its value rose. To dissuade such speculation, prior appropriation includes the principle of beneficial use. This doctrine became instituted partly because the people wanting to use water, or any other resource, were the ones on the ground, and it was impractical or impossible at the time for some entity to actually enforce property rights from afar. But using Western resources also meant developing them, which was the goal of nineteenth-century land policy.

In 1922, the seven states in the Colorado River basin met in order to allocate the river among themselves. The mighty Colorado and its tributaries, they estimated, held about 16.5 million acre-feet (MAF) per year, or about 5.4 trillion gallons. After months of contentious negotiation, the Upper Basin and Lower Basin would each get 7.5 MAF, leaving a comfortable amount of water to flow through its natural channels. Mexico, which had been entirely left out of the negotiations, cried foul. Revisiting the Colorado River Compact in 1944, Mexico gained 1.5 MAF, and in wet years the Lower Basin would get an additional 1 MAF--leaving little or nothing for the natural environment.

Put simply, there just isn't that much water in the Colorado. Estimates were based on a few unusually wet years. Through the twentieth century, the average yearly natural flow was closer to 11 or 12 MAF. Water experts Eric Kuhn and John Fleck wrote a book, Science be Dammed, that outlines how these and other negotiations ignored contrary science rather than risk frustrating the region's political demands. To be honest, I haven't read it yet, because I don't need much convincing on that score. The 1930s saw the devastating droughts that caused the Dust Bowl, and I find it hard to believe that no one in the wake of that disaster imagined that their measurements might need to be revisited.

The Colorado River Compact has been "the Law of the River" for a century now, though the consequences have been rather predictable. Not only did it overallocate the river's flow, it incentivized the states to compete with each other in using their respective portions. Remember, beneficial use is part of the law; water rights are only secure if they're being used.

The Colorado River Compact is of a piece with the Progressive conservation mandate to order and develop the country's resources. The development of a river system that can be metered and divided year over year is no insignificant feat, and the decades of dam building that would come after World War II represent the creation of a mechanism not just for moving water to where it was desired but also for its accounting--turning ecosystems into something that can be forecasted and tracked on spreadsheets.

The Colorado River system does not make up the entirety of the West's water, but the motivation to use its water before one's neighbors would come to place it at the region's center. To borrow the term from Richard White, the river system is now an organic machine, a great cyborg of reservoirs, canals, aqueducts, pumping stations, and all the attendant machinery and bureaucracy which exist to rationalize this organic, dynamic entity--to turn it into something both within and apart from its natural setting. And yet, once again, Western water policy was based on pseudo-science. The Colorado River Compact distinguished itself only superficially from the motto that "rain follows the plow." The impulse to declare that there is as much water as we want there to be has followed us from the nineteenth century through the twentieth and into the twenty-first century.

Still, putting a finite number on the river, even though it was fanciful, led to the heritage of conflict and litigation that John Wesley Powell predicted. Utah is currently in the middle of an attempt to avail itself of Colorado River water that it says it is owed, while the other Upper Basin states object. Arizona and California have had perhaps the most intense rivalry. Arizona refused to ratify the compact until the 1944 renegotiation. One of the results of several lawsuits between those states resulted, at long last in 1983, in the Supreme Court declaring that Native Americans' water rights in the basin finally be recognized. Predictably, none of the 29 tribes in the basin were included in the Compact.

The Compact made it 101 years before it reached the point of collapse. Amid two decades of a megadrought, Lake Powell and Lake Mead approached "dead pool" in 2023, at which point water would not be able to flow through their respective dams. This would mean the dams' hydropower would vanish, and the river's water would no longer flow to downstream consumers. The Bureau of Reclamation announced that it was considering the unprecedented step of curtailing water rights, if needed, in order to preserve the function of the system as a whole. While it may seem perfectly logical that Reclamation, which built and operates the system, would consider turning the faucet off, people familiar with the topic of water in the West will understand the alarm that the announcement caused.

Advocates for the decommissioning of Glen Canyon Dam (which forms Lake Powell) have begun to lean into the argument that such a move is inevitable. It's a very convincing argument. Though a remarkably wet winter filled up the region's reservoirs for however longer, the states are still racing, as they have been for a century, toward the bottom of Lake Powell, with each state vying to be the one to drink the river's last drop.

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the ProblemCurb" (1891 - 1945)