"Our Last Major Water Resource" -- The Central Utah Project

In 1965, governor of Utah George Clyde referred to the Colorado River as "our last major water resource." He was correct about this, but his estimation that it would be "key to development of Utah's resources for the next 100 years" has fallen far short.

The Central Utah Project (CUP) was a continuation of Reclamation's purpose: to open up new land through irrigation. It was, more or less, an expansion of the Strawberry Valley Project. But while there is considerable continuity from that project to the CUP, the size and scope and politics of the post-World War II Bureau of Reclamation marks a shift into a different era.

From the beginning of the Reclamation Service until the New Deal era, budget deficits plagued Western reclamation. To return to a theme, this is because irrigation is very difficult in the West. But the federal government was also developing projects that private and state efforts lacked the money for. Opening new land, in 1920 as in 2020, was a matter of measuring costs and benefits -- the limits were and are a matter of finances and practicality, influenced but not wholly determined by geography. As time went on, the curve of cost and difficulty steepened. Private and state efforts, which already had a foothold in the most easily irrigable lands, continued apace and developed more water than Reclamation during the first few decades of the twentieth century.

Engineering in the twentieth century opened new possibilities. Water infrastructure sought to accomplish several things. For one, rivers and streams in the West tend to be largely fed by snowpacks in the peaks of mountains. This means that flows are seasonal -- rivers are engorged in the springtime as the snows first start to melt, and the same waterways are trickles by the end of summer. A crude earthern dam will store water as a reserve against dry years, but it will also smooth out the seasonal variation in supply. Canals and diversions can then be built off of the waterway itself or out from a reservoir. These conveyances can bring water to arable land. The Strawberry Valley Project, for example, brought water from the Uinta Basin and diverted it to otherwise unreachable benchlands in Utah Valley. Unlined canals will "lose" water as it is absorbed into the earth, so upgrading these canals by lining them with concrete exists as a possbility. With the invention of hydropower turbines in the late nineteenth century, water projects could incorporate electric pumping stations to move water vertically. Alternately, engineering prowess can be applied toward the digging of tunnels through mountainous areas.

Sophisticated engineering, geological expertise, and construction techniques allowed for bigger dams. This meant more storage -- more of the rowdy Colorado's flow regulated and kept in reserve -- but it also meant abundant hydropower. Electricity around the turn of the century was for big cities and industry, but the New Deal saw the federal government bringing electrifrication to rural areas around the country. The Bureau of Reclamation built the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River and the Boulder Dam on the Colorado (later renamed the Hoover Dam) to provide hydropower to nearby cities. Crucially, the capacity to sell hydropower to households gave Reclamation what it desperately needed: paying customers.

With Reclamation's budget difficulties at least partially sorted out and with truly awe-inspiring feats of engineering like Hoover Dam within its abilities, the bureau went on a dam-building spree through the 1950s to the 1980s. The Army Corps of Engineers, which had historically only tackled water projects east of the Mississippi, even got involved with Western projects.

The federal government was picking up the tab and providing the muscle, and the Western states were eager to claim their share of water under the Colorado River Compact. Utah's plans began in 1939 with a proposal titled the Colorado River-Great Basin Project, which called for an interbasin transfer of 1 million acre-feet. Utah's population center and its best agricultural lands were over the divide in the Great Basin, though the state's new spoils were in the Colorado. This proposal, however, was so ambitious that even in a greatly reduced form, renamed the Central Utah Project, it needed to be approved as part of a regional plan: the Colorado River Storage Project in 1956. The legislation that approved this plan also included the Glen Canyon Dam and Flaming Gorge--both of which would become major suppliers of hydropower as well as recreational sites.

The initial phase of the CUP included four units. Two of the units, the Vernal and Jensen Units, were relatively small. Construction began soon after the approval of the CRSP. The Bonneville Unit, the centerpiece of the CUP, was much larger. Initial planning and water rights negotiation took a decade, with groundbreaking on the Starvation Dam (one of several systems within the expansive Bonneville Unit) happening in 1967.

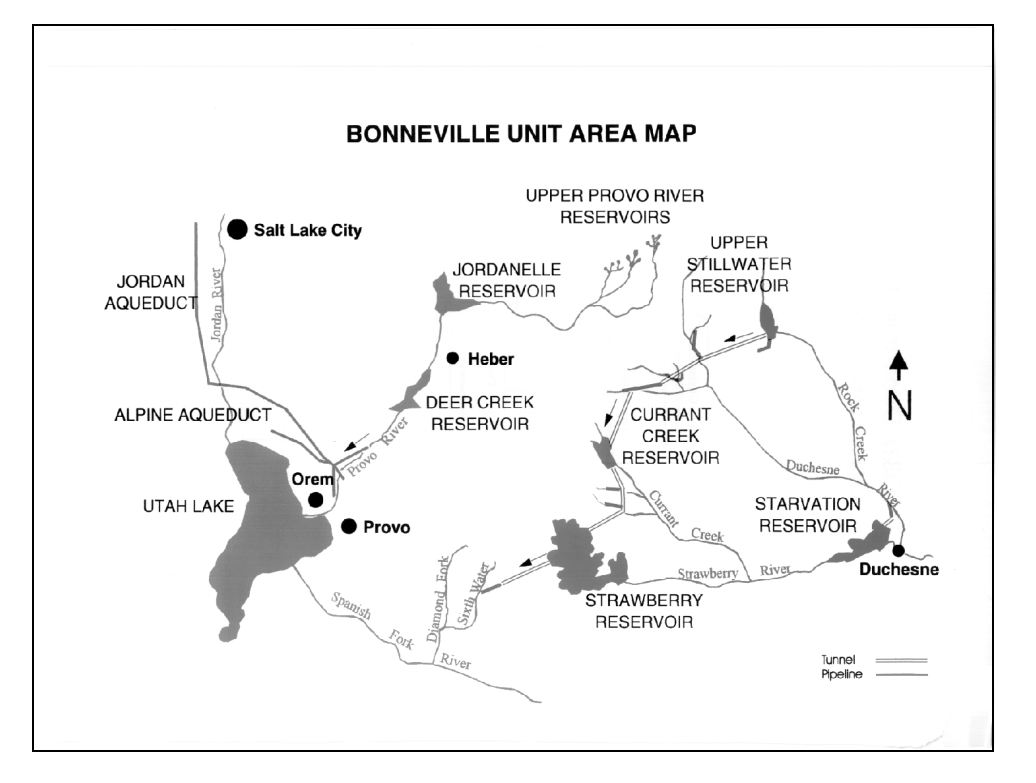

The Bonneville Unit, named for the target of the interbasin transfer, the Bonneville Basin on the Wasatch Front, built off of the foundation of the Strawberry Valley Project to transfer around 136,000 acre-feet of water annually. The Bonneville Unit consists of several different connected systems which collect water from tributaries of the Green River and feed into an enlarged Strawberry Reservoir. It also stores water from the headwaters of these rivers in the Uinta Mountains and channels them to Utah and Salt Lake Counties through the Provo River.

|

|---|

| Bonneville Unit |

The relatively protracted planning process of the Bonneville Unit would only be the prologue to a development proceeding in fits and starts. Indeed, the unit is still not finished, with the Utah Lake System scheduled to be completed in 2026. As planners were putting together the authorization of the Bonneville Unit, they needed the approval of the Northern Ute Tribe for water rights from the Duchesne River. An agreement was made in 1968, with congressional approval for the Colorado River Basin Project Act, in which the Ute Tribe would defer their water rights in exchange for two additional units that had been drafted: the Uintah and Ute Units. Congress did not approve the Ute unit, but a compromise resulted in some of its elements incorporated into the Uintah Unit.

None of the units planned for the benefit of the Utes were built (though for accuracy's sake, the Upalco and Uintah Units would have also supplied non-Indian farmland). The Bureau of Reclamation built the Moon Lake Project in the Uinta Basin in the 1940s to replace Ute water that had been appropriated by settlers during the allotment period, but by the 1960s, Indian water development was a much lower priority. Construction of the Bonneville Unit ran significantly over budget, which led to increased scrutiny by the end of the 1970s. The failure of the Reclamation Service to collect on its construction debts turned into a habit, in the post-war period, where the Bureau of Reclamation would submit a low estimate to gain Congressional approval and then ask for more funding once a project was underway. New environmental regulations passed during the 1970s also added to the expense and administrative burden of construction projects. The entire CUP, at its approval in 1956, gained an appropriation of $760 million. By 1985, the Bonneville Unit alone had spent more than $2 billion.

Political pressure mounted against the CUP through the 1980s. President Jimmy Carter, in the late 1970s, drew up a hit list of wasteful Reclamation projects, with the CUP near the top. Even within Utah, opinions were divided. Environmentalists raised objections. The environmentalist movement, after all, found its legs by organizing against Western dams. The CSRP originally targeted the scenic Echo Park, and Reclamation changed plans after a national outcry. While environmental groups such as the Sierra Club were less successful in saving Glen Canyon from being inundated, dams remained a rallying point. At the same time, a coalition of Utah's formidable sport anglers also protested the potential of the project to diminish their favorite fishing spots. And while the CUP was always meant to funnel water toward municipal and industrial water systems in Utah and Salt Lake Counties, Utah County was urbanizing -- its fruit orchards and sugar beet fields were turning into subdivisions as the Bonneville Unit was being constructed. Rural water was flowing to quickly growing urban areas, and white farmers in the Uinta Basin cried foul.

|

|---|

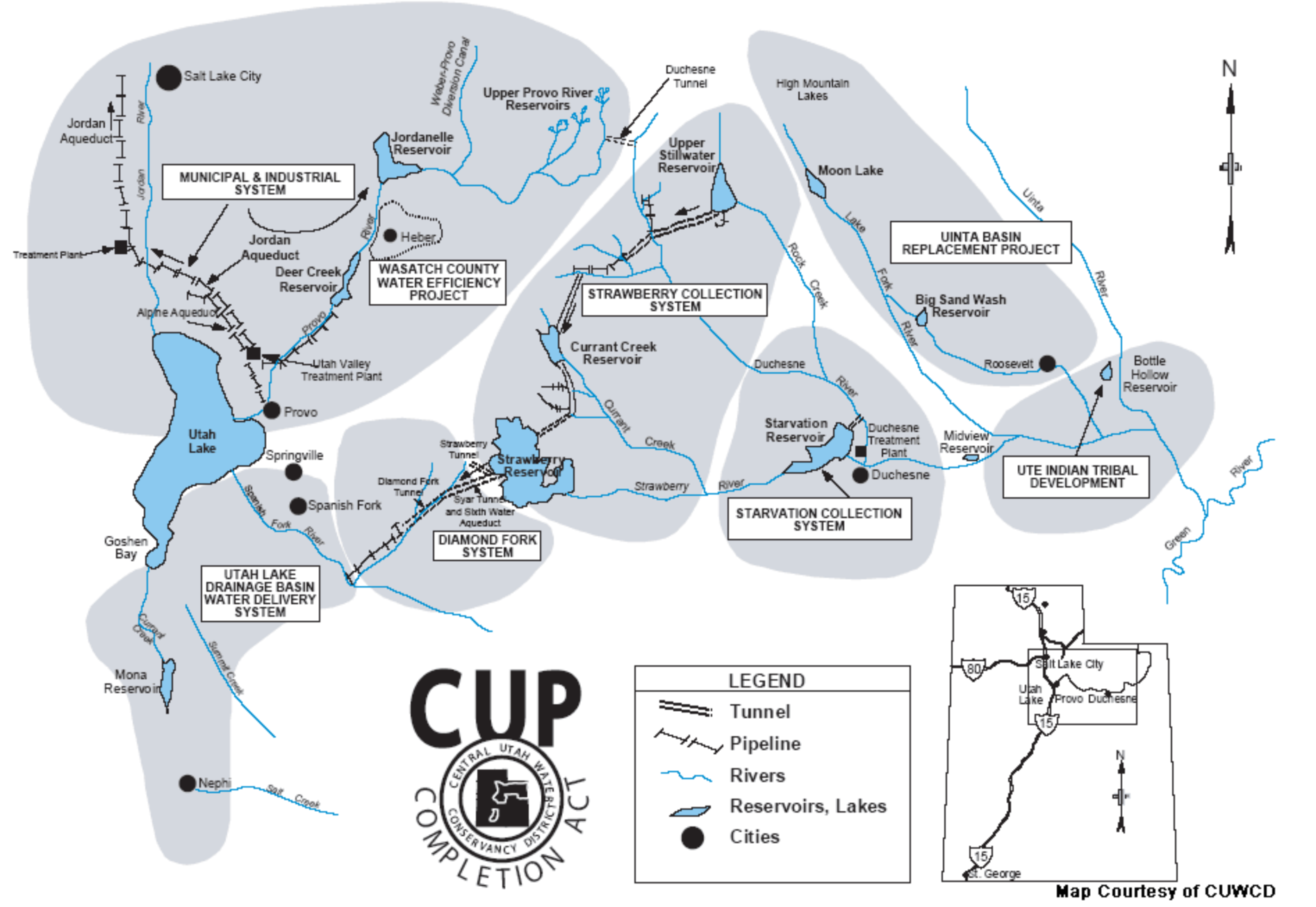

| Portion of the Central Utah Project relevant to the Central Utah Project Completion Act of 1992. The Vernal and Jensen Units are left out here, but would be to the east. Much of the water infrastructure pictured -- Starvation, Strawberry, and Diamond Fork Systems -- funnels water to the Wasatch Front. Also note the relative size of the "Ute Indian Tribal Development." |

Most significantly, the slow progress of the Indian units caused the Ute Tribe to grow disenchanted. Considering the history of the Uintah Indian Irrigation Project and the Strawberry Valley Project, the willingness to even negotiate in the 1990s demonstrates considerable patience. Facing an uncertain future, the state of Utah assumed responsibility for the CUP with the Central Utah Project Completion Act of 1992, though the Department of the Interior was still responsible for funding. The Utes agreed to the new terms, but by 1999, the Tribe rescinded its support. The cash settlement of $198 million that the Tribe received from the 1992 act was some comfort, though political scientist Dan McCool notes that the comparatively large settlement was "basically a liability payment" intended to shield the government from its failure to live up to the 1965 deferral agreement. And the money is not water. The Tribe continues to pursue lawsuits over water.

The Central Utah Project developed a lot of irrigation water for eastern Utah in addition to the water piped into the Great Basin, much of it for municipal and industrial usage. The amount of water that flows to the Wasatch Front is not insignificant, but relatively speaking, it is not a large amount -- about a tenth of the annual flow of the Bear River or a third of the Jordan River. Conceptually, the project represents the awkwardness of drawing a state across two major watersheds. But it also represents another phase of the state's population and power center expanding its footprint into another valley, another chapter in the history of Great Salt Lake running through the Uinta Basin.

References:

Reed R. Murray and Ronald Johnston, "The History of the Central Utah Project: A Federal Perspective" (US Committee on Irrigation and Drainage, 2001).

Donald Pisani, Water and American Government: The Reclamation Bureau, National Water Policy, and the West, 1902-1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water (New York: Viking, 1986).

Craig Fuller, Robert E. Parson, and F. Ross Peterson, Water Agriculture and Urban Growth : A History of the Central Utah Project: The CUP: The First Fifty Years 2016. Salt Lake City Orem: Utah Historical Society ; Central Utah Water Conservancy District.

Craig Fuller, "The Central Utah Project," in Utah History Encyclopedia

Dan McCool, Native Waters: Contemporary Indian Water Settlements and the Second Treaty Era, (Tucson: University of Arizona, 2002).

Read more:

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

[Note: this post was edited 3/25/2024 to correct the year that the Ute Tribe finally rescinded support of the CUP from 1998 to 1999 and to clarify and add additional context for the CUPCA settlement.]