Water for City and Country in the late 20th century

The last major Colorado River projects were approved in 1968. The Bureau of Reclamation declared twenty years later that the "arid West essentially has been reclaimed." For at least a few decades now we have been in a new era of Western water. How do we make sense of it? I've argued that it is important to consider the fates of urban and rural places as intertwined when it comes to water. The last fifty years show that that continues to be true.

As you might imagine, planners knew that the development of surface water supplies could not go on forever. Utah made an inventory of water resources by county in the early 1970s. For Salt Lake County, the report found: “[Since 1960] the needs of the increasing population have been met by providing a small amount of surface storage, transferring water from irrigation to municipal use, exchanging water of poor quality for water of better quality, importing water from outside the county, and withdrawing substantial amounts of ground water.” "Transferring water from irrigation to municipal use" would continue to be very important to urban water supplies around the region.

Imagine a farmer has twenty acres and uses 3 feet of water per acre every year: the total consumption is 60 acre-feet of water (for simplicity's sake we'll pretend that all of the diverted water is consumed, which is usually not the case). The average urban household uses roughly half an acre-foot of water per year. So if that farm is sold to real estate developers and one hundred people move in (consumption totaling 50 acre-feet per year), there is a net reduction of water consumption by 10 acre-feet per year even though the population grew considerably. Again, this is just a theoretical example, though these figures shouldn't be dramatically out of line with the real world.

With the region continuing its post-war boom and the end of Reclamation's dam-building spree in sight, it is not too surprising that Western cities would be looking to agricultural land as the next source of water (in addition to a slightly more diversified slate of new water sources). Colorado governor Richard Lamm wrote in 1976,

It seems clear to me that we are in a transition period moving from the development and storage of water to a period which will be characterized by management and distribution. This new era will be characterized by increasing conflicts between the agricultural use of water and the transfer or attempted transfer of agricultural water to municipal, industrial, recreational, and other environmental uses. We will not be as preoccupied with the development of new water supplies as we have been in the past.

Lamm was prescient about the subsequent period of "management and distribution." As for the conflict between agricultural and municipal water, that requires a bit of nuance.

Colorado's Front Range cities, in order to meet the water demands of fast-growing cities like Denver, Boulder, and Fort Collins, engaged in "buy-and-dry" practices significantly by the 1980s. The Front Range is not unlike Utah's Wasatch Front--home to a string of cities and sprawling suburbs that are outside of the Colorado River Basin. Utah's Central Utah Project is analogous to the Colorado Big-Thompson Project, though the latter came earlier and moves a vastly greater amount of water into the other major watershed. Anyway, buy-and-dry is when municipalities buy water rights from farmland, near or far, leaving the land to go fallow or to dry up entirely. These are voluntary, market-based transfers of water rights, though the profound social and environmental consequences have saddled buy-and-dry with negative connotations. Selling water rights in this way can ruin an entire farming community overnight, and fallowed farmland can become overrun with weeds or turn to dust. Colorado's state water plan in 2015 addressed the practice, expressing a goal of avoiding it.

Tucson also experimented with buy-and-dry in the 1960s and 1970s, with similarly negative results. By contrast, Phoenix expanded its water supply in a more organic way. Real estate developers (not the city itself) bought land along with water. One report found that the transfer of agricultural to municipal water "is now occurring automatically as the cities envelop the agricultural lands surrounding them. For instance, the Bureau’s Salt River project supplies almost three-quarters of Phoenix’s water because the city has expanded onto former project-irrigated lands.” Urban development in Utah has followed this path.

By the 2000s, Tucson seems to have settled into a similar approach. A group of sociologists, authors of the book The Field of Water Policy: Power and Scarcity in the American Southwest, recently found that these "market-based" transfers of water and land (buy-and-dry is also market-based, but I find this terminology handy, if not strictly accurate, in differentiating these approaches) were beneficial to both city and country and avoided political backlash. Since the 1970s, suburban development is “integrated into the agricultural heritage of a small, neighboring town… This style of development takes advantage of the gradual disappearance of agriculture. Agricultural land can be left fallow in times of aggravated drought, thus helping to preserve groundwater reserves while at the same time safeguarding it at the margins in order to protect the myth of a ‘pioneering’ past.” This also provided an opportunity for farmers to get money from land: "Land-use conversion strategies rapidly took into account both the crisis in agriculture and the issue of urban development: families of migrant farmers became investors and waited for the right moment to sell their land to developers." This sounds pretty similar to historian Richard Hofstadter's description of the nineteenth-century homesteader: "harassed little country businessman who... gambled with his land."

Cultural critic Andrew Ross also identifies this dynamic in contemporary Arizona:

Over time, and as a supplementary water supply from the Colorado River [the Central Arizona Project] was tapped to guarantee new housing construction from the 1980s, an understanding took shape. The first priority of [Arizona’s] water management was still to service agriculture... But since the most profitable use of land lay in housing development, water resources would switch over to urban use as and when the farmland was converted. In the event of shortages like an extreme drought, the farmers’ water would summarily be reallocated for urban use. Since the growers used more water per acre than a housing subdivision would, the agricultural quotas were an insurance policy for the future growth of the metropolis, and farming was a temporary form of capital investment that would see its full dividend after the surveyors, bulldozers, and drywallers had pushed the urban fringe a few miles further out. The interests of farmers and developers were both well served by this understanding… As long as the overall water supply was assured, and housing sales were healthy, there was no reason to question the formula.

As Colorado water official Brian Werner put it, "There are farmers that look at their water supply as their 401K, it is how they're going to retire." It's not as complicated as it may appear: farmers want the option to sell their land; they do not want to be forced to sell their land.

In 1990, the authors of Utah's State Water Plan wrote, "Utah's policymakers must... decide if water will be used as a growth management tool. This plan assumes it will not." Subsequent plans have not included similar language; Utah's policymakers decided, one way or another, that water would not be used as a growth management tool. But for about twenty years or so, water planners were unsure what growth would mean for their cities. Then, for many, water concerns largely faded from view until about the 2010s.

So what exactly happened in the interim? In writing about this topic, I wanted to demonstrate how the concerns of urban and rural places are intertwined, for one. But I also wanted to historicize the ongoing large-scale transfer of agricultural to municipal water. So, part of the way that planners allayed their fears involved this transfer, and a shift away from the controversy around buy-and-dry helped to take water out of the spotlight.

A number of wet years in the 1980s played a huge role in taking people's minds off of water. Great Salt Lake reached its highest recorded level at this point, and the threat of it "overflowing" onto I-80 led to the construction of massive pumps costing $60 million, redirecting water to the salt flats to the west where the water would evaporate. The pumps haven't been used since 1989. (Many side-by-side comparison photos of Great Salt Lake's water level will show the level at these record highs next to the record low in 2022, which I think is a little misleading. Something to be aware of.) But my point is that these wet years filled the region's reservoirs to bursting.

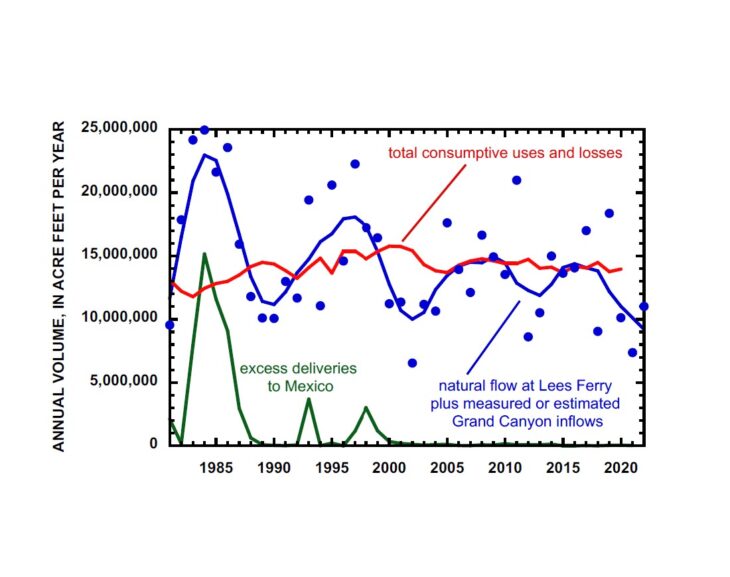

This graph of water use and supply, by Jack Schmidt, John Fleck, and Eric Kuhn, shows how much water was in the Colorado River System in 1985--about 23 million acre-feet. This was an enormous anomaly--the supply between 2020 and 2022 averaged 9.4 million acre-feet per year. For a decade or so, it was impossible for water users to consume all that water. Reservoirs released water into the ocean to keep from overflowing. Unfortunately, the structures of our water systems are not very good about planning for the future. We rather quickly squandered this enormous surplus. (Graph below by Jack Schmidt, Utah State University) Update 2/6/2025: I caught myself making an analytical error here. These structures are actually keenly interested in planning for the future, just not for maintaining the region in a state of population or economic stasis. This is the "piggy bank" metaphor that I counter in a more recent post here. It is better to think about this water infrastructure as a lending bank instead, in which case the purpose of the bank is to move this water towards investment and development.

As Schmidt, Fleck, and Kuhn write, "When the Colorado's flow was up, we used it all. When it was down, we drained the reservoirs... And during the few stretches of somewhat higher flows, we did not significantly refill the reservoirs." Instead of keeping the reservoirs full, we collectively put water out of our minds. Update 2/6/2025: the average person grew less alarmed about water as reservoirs filled back up in the mid-1990s, then slowly became aware of the problem again by about the mid-2010s, but planners and managers have naturally been looking to the future -- less urgently still in wet years than dry years.

References:

G. Hely, R. W. Mower, and C. Albert Harr, “Water Resources of Salt Lake County, Utah” (US Geological Survey in cooperation with the Utah Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Rights, 1971).

Richard D. Lamm, "Colorado, Water, and Planning for the Future," Denver Journal of International Law & Policy 6 no 3 (1976).

C.B. Cluff and K.J. DeCook, "Conflicts in Water Transfer from Irrigation to Municipal Use in Semiarid Environments," Water Resources Bulletin, 11 no 5 (Oct. 1975): 908-918.

Richard L. Berkman and W. Kip Viscusi, Damming the West: Ralph Nader’s Study Group Report on the Bureau of Reclamation (New York: Grossman, 1973).

Franck Poupeau, Brian F. O’Neill, Joan Cortinas Muñoz, Murielle Coeurdray, and Eliza Benites-Gambirazio, The Field of Water Policy: Power and Scarcity in the American Southwest (New York: Routledge, 2020).

Andrew Ross, Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

**Read more:**A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water