There is No Shortage of Water

This post is an attempt at a short explanation of the problem with water in the US West as I near the end of a multi-year project researching and writing. I came to this topic in the fall of 2021 as Great Salt Lake dried to its lowest historic level the following year. At that time I became a founding member of the group Save Our Great Salt Lake, and I had been studying and writing about Utah's water history for work. I was on Save Our Great Salt Lake's governing committee for a year.

My motivation for studying this topic began with a desire to find a political solution for the purposes of organizing. Over time, as I found some of the conventional wisdom about the issue to be unsatisfactory, the scope of my research expanded. As a result, this project is a sketch; this is about as much as I can do on my own. Still, I think it's valuable to share what I've done.

The key to understanding water shortages in the West is to understand that the region and the country views water first and foremost as a necessary element for accessing and developing land. Water is only scarce relative to the abundance of undeveloped land.

John F. Kennedy once said, "Anyone who can solve the problems of water will be worthy of two Nobel prizes--one for peace and one for science." But at the risk of sounding like a zen koan, water is not the problem in the water problem. There is no shortage of water. Fresh water falls out of the sky. Treating water as the problem only compounds the problem, in that it accepts the premise that there is some quantity of water that will satisfy the demands of the country for its aims in the West. The truth is that amount of water does not exist, not even with the fanciful, environmentally damaging, and electricity-hungry schemes that people continue to dream up.

Framing Western water in this way turns it into a symptom of the contradictions in a much larger structure. The question becomes, how valuable to this structure is expansion in the West? Can the structure adapt without continuing to exhaust the region's available water?

There are a number of motivations for the ongoing colonization of land in the US West. The Reclamation Act of 1902, which laid the foundation for the federal agency that would reshape the hydrology of the West, came as part of a series of legislation meant to encourage settlement through homesteading. Traces of Manifest Destiny can be found in the determination of the federal government to commit, and recommit, funds to the development of increasingly marginal tracts of land. The frontier has long played a significant role in the American mythos; retreating from its challenges because of aridity would have struck many people as absurd or mortifying at one point in time. In a similar vein, the development of land -- "reclaiming" the desert waste to make it productive -- plays a significant role in justifying the dispossession of Indigenous peoples under settler colonialism. Along with a deeply rooted bias against arid lands, this motivation is linked to an impulse to transform the desert.

Not all motivations are ideological. In the late nineteenth century, railroads, land speculators, and Western politicians pushed for generous land policies and promoted Western settlement to increase their wealth or influence or both. The expansion of markets across the continent was seen as a valuable way to augment the country's wealth during the debates over the Reclamation Act. In the twentieth century, as the Bureau of Reclamation became more powerful, Westerners welcomed the federal government's capital investment in the region. This investment invited business and raised property values. Established corporations took advantage of the region's low cost of living, natural amenities, low union density, and lax regulations to expand operations or to relocate.

Additionally, I contend that the expansion of material wealth that has occurred in the region as a result of water development projects has contributed to political harmony that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. This can be seen fairly clearly in the differing interests between urban and rural residents. When water is abundant, neither party is much concerned about their relative share of resources. When water (or money for water projects) becomes scarce, the rifts become more visible. At the risk of over-extrapolating, there is a phenomenon that seems to correlate. As the mean population center of the country moved west, antagonism between capital and labor (such as animated political discourse in the first half of the nineteenth century) diminished.

In keeping with this analysis, the current wave of water angst, beginning in the mid-2010s, has urbanites tending to single out agriculture as the cause of the problem. This critique is ahistorical and downplays city dwellers' enthusiasm for federal water development projects. However, when this phenomenon is seen holistically, the singling out of agriculture demonstrates continuity with an older idea of Western development in which farmers break ground to eventually be bought out by cities.

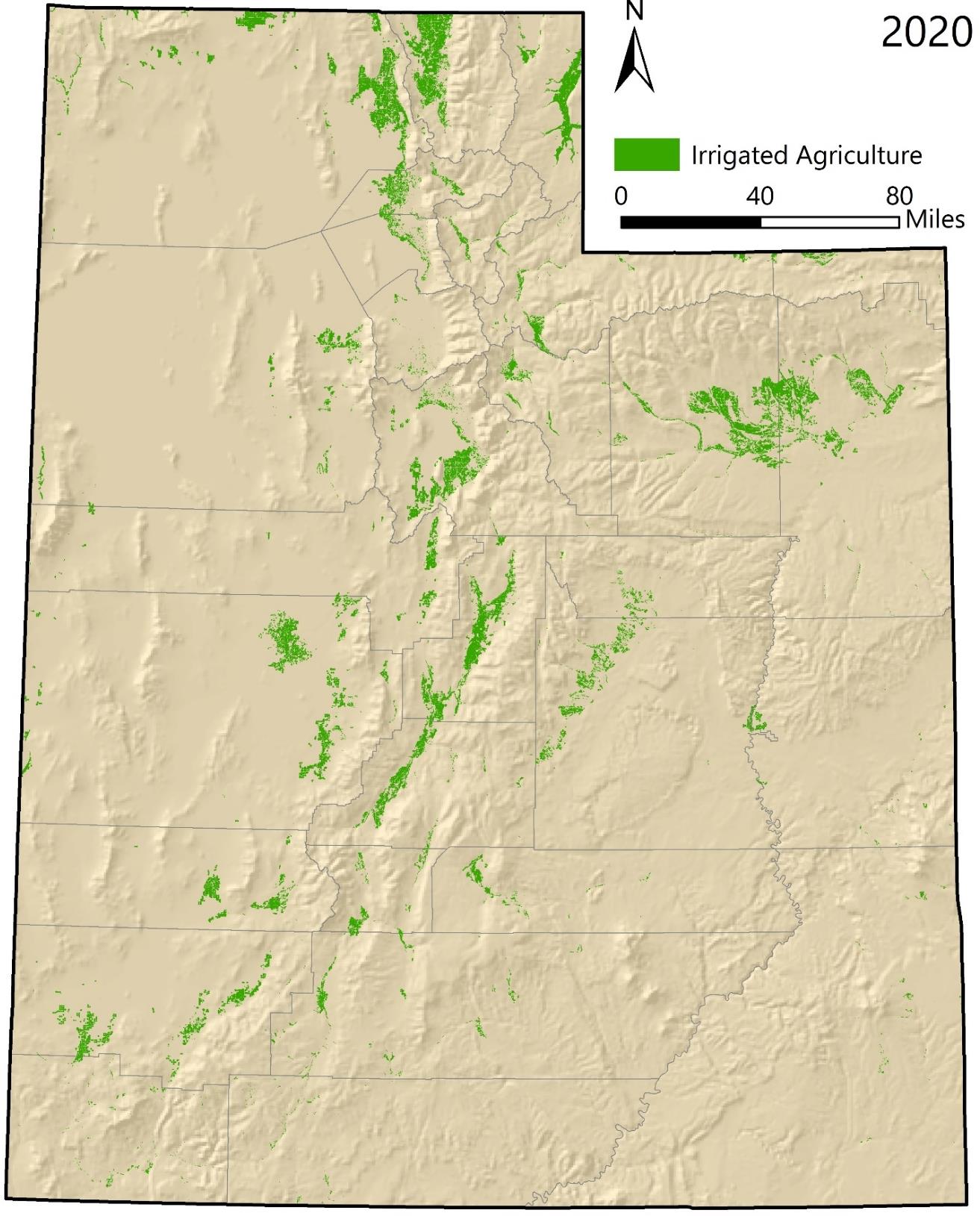

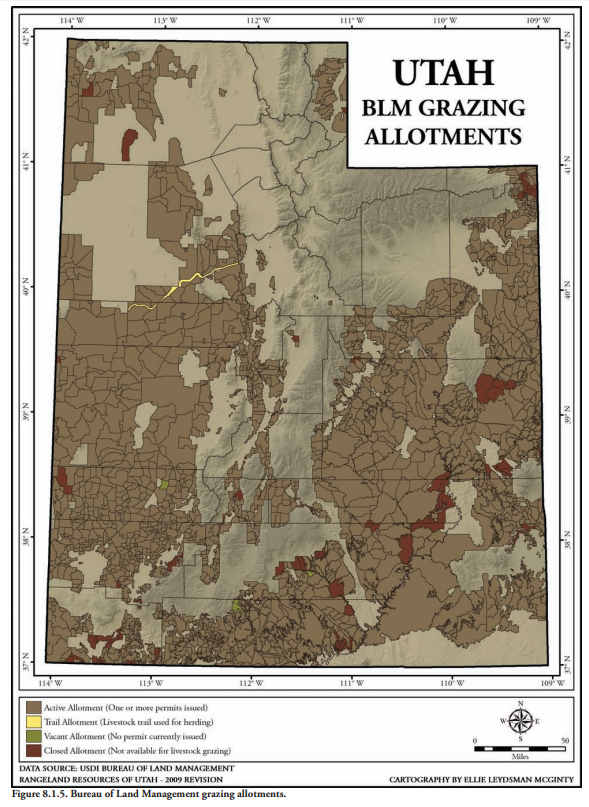

Much critique of irrigation water systems in the West tends to focus on lucrative vegetable growing operations in California and extrapolate outwards. This is somewhat reasonable, as California has the most lucrative agricultural sector in the country and supplies the vast majority of the country's winter vegetables. However, the West is a large region, and agriculture is not monolithic. Alfalfa has become the dominant crop in the broader West, including in parts of California. This happened over the course of the twentieth century as farmers pivoted from growing fruits, vegetables, and nuts towards supporting the region's livestock industry. In the Mountain West especially, beef and dairy cattle dominate agriculture, and hay and pasture dominate cropland as a means to supplement public lands grazing. This is not because alfalfa hay is particular lucrative, but because it has particular virtues that make it a good feed crop to grow in the arid West, even for lifestyle or retirement farms. Cattle are economically important to the region (though the importance in the aggregate is less so than the importance to some rural towns), but the industry is important particularly as a way to use land.

An emphasis on land directly confronts fundamentally American hopes for the West as a region. The Jeffersonian ideal looms large here, perhaps more than anywhere else in the country. Yet a country that pinned its hopes on eternal expansion was bound to be reach a crisis point eventually. The era of "free water" extended the promise of "free land," but now both are coming to an end whether we like it or not.

This Jacksonian democratic ideal also depends on a settler colonial structure that continues to deny water to Western Indigenous nations. In other words, wealth has not been created so much as stolen. If this is at the root of the problem, as I believe it is, then the solution to both the injustice of settler water grabs and to our unsustainable schema of expansion is to give the water and land back. In my opinion, this should guide long term goals for Western water, though in the meantime, most available options should be pursued due to the urgency of some environmental impacts. Measures that would unnecessarily provoke a backlash among rural agricultural areas, however, should be avoided where possible, as agriculture holds most the most senior water rights in most areas. Cooperation across sectors is key.

In conclusion, many observers have been trying to craft a solution by assuming that it is possible to rationally allocate water here, something like balancing a household budget. My analysis is that there has never been a rational approach to Western water. Regional and national goals have long been grounded in teleogical and often expressly religious thinking, self-interested plunder, environmental injustice, and contempt for the natural environment. These are the hurdles that we need to confront directly before we can craft any kind of sustainable water program for the region.

**Read more:**

A Short History of Water in the US West

The Agrarian Foundations of the Western Water Crisis (1620 - 1902)

The 100th Meridian: Where "Free Land" Requires "Free Water" (1862 - 1923) How (Not) to Make the Desert Blossom as the Rose (1847 - 1860)Free-for-All in the Uinta Basin (1879 - 1920)

Race to the Bottom -- The Law of the River

The Sinful Rivers We Must Curb

Our Last Major Water Resource -- The Central Utah Project

The Case of Uphill Flowing Water

Water for City and Country in the Late 20th Century

What's the Deal with Water Marketing

Expansion is at the Root of the Problem

Racism in Environmentalism and Why it Matters