Agricultural to urban land conversion

I have been thinking about the broad historical progression in the West from farmland to city, as per usual. (We could even back up a bit more, all the way to the 1820s, and think about forts and fur trading centers in their role as colonial outposts. But, as with mining towns, these did not tend to develop directly into the Western cities that we have today.) So with this grand sweep of history in mind, I was curious what the progression of land use changes looks like when zoomed in.

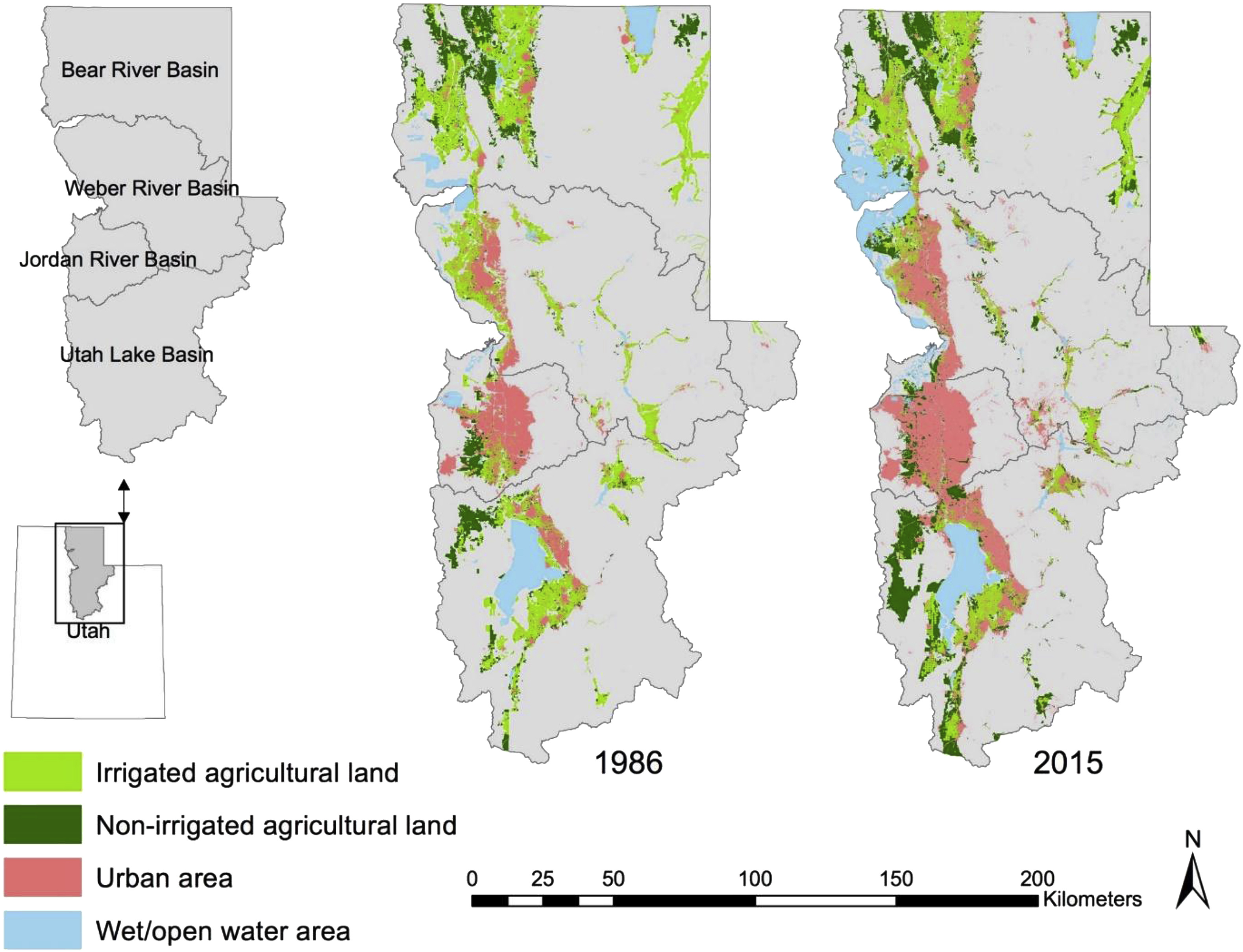

This article by Enjie Li, Joanna Endter-Wada, and Shujuan Li about agricultural land development in Utah is a good starting point. For one, it provides numbers and visuals for how residential growth affects agricultural land.

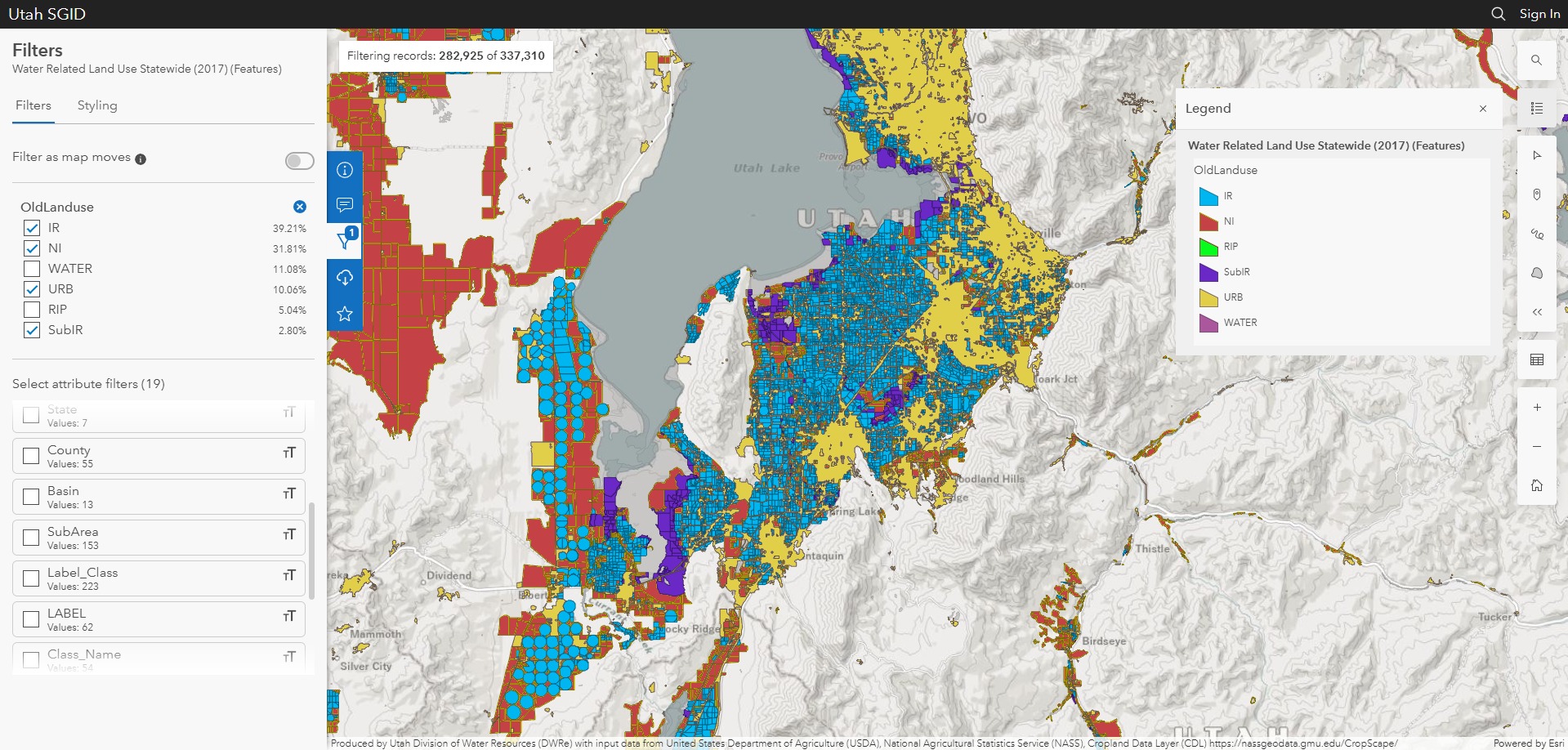

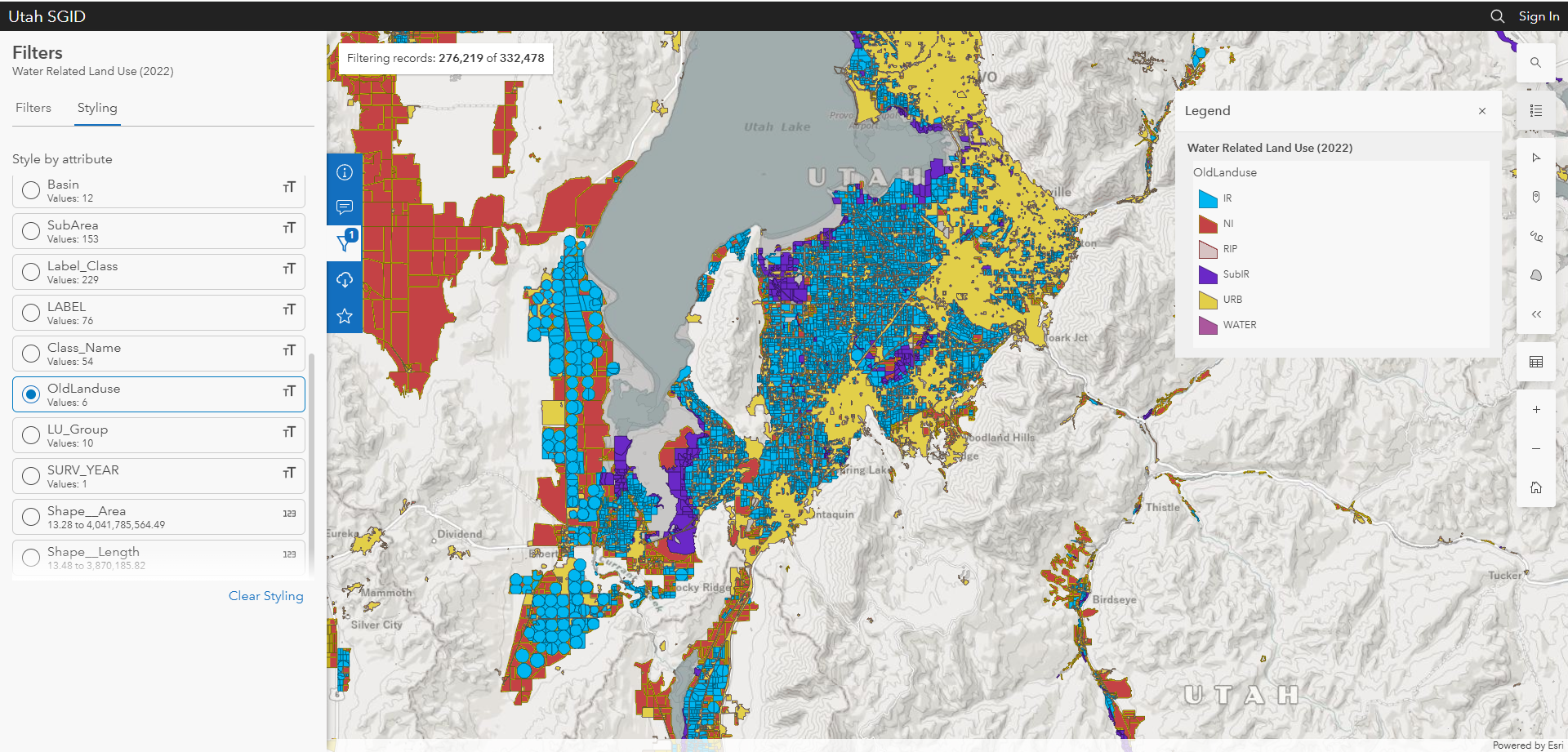

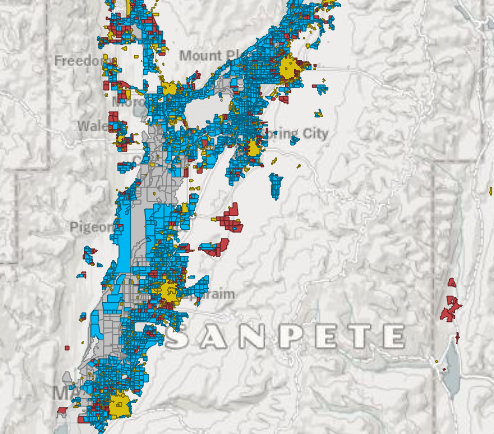

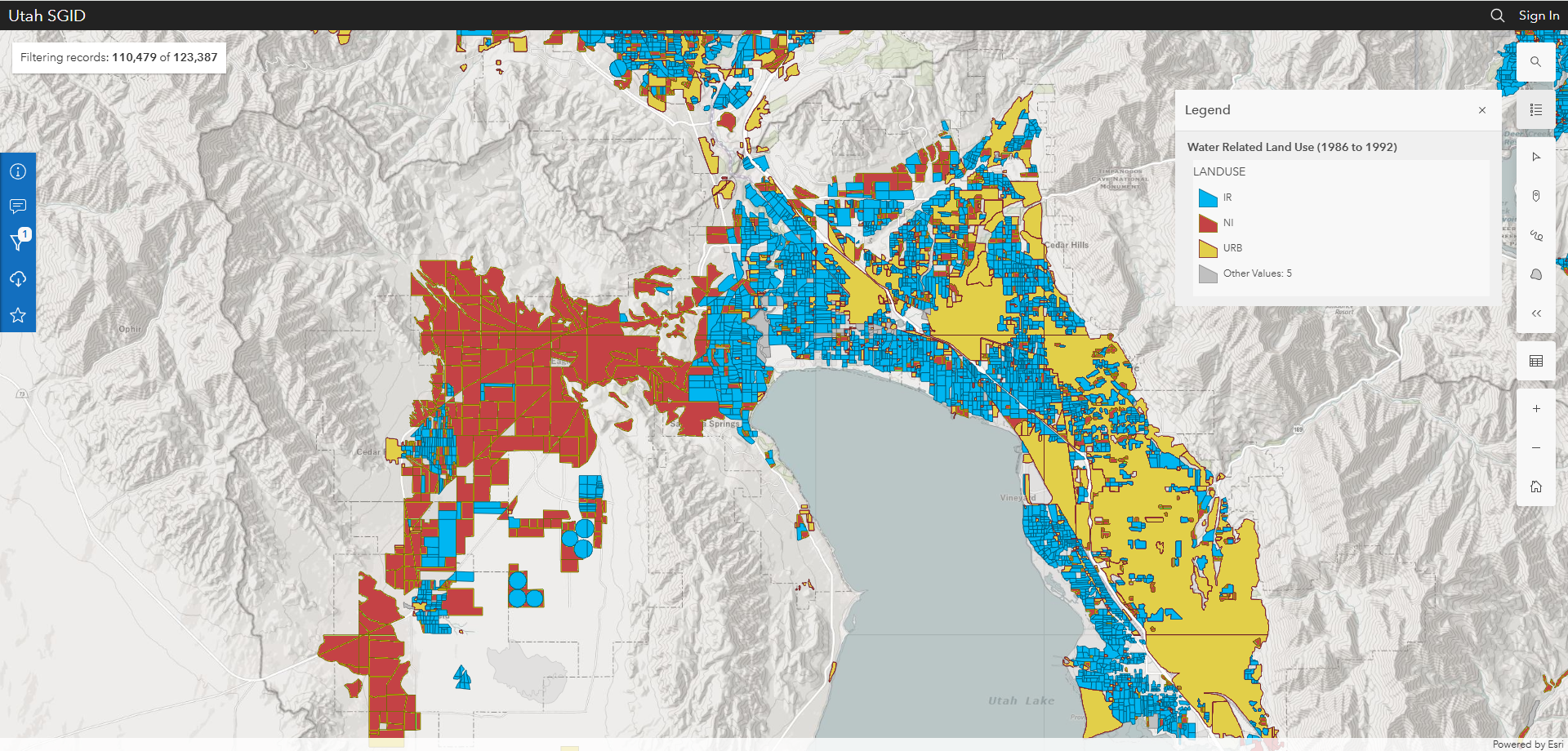

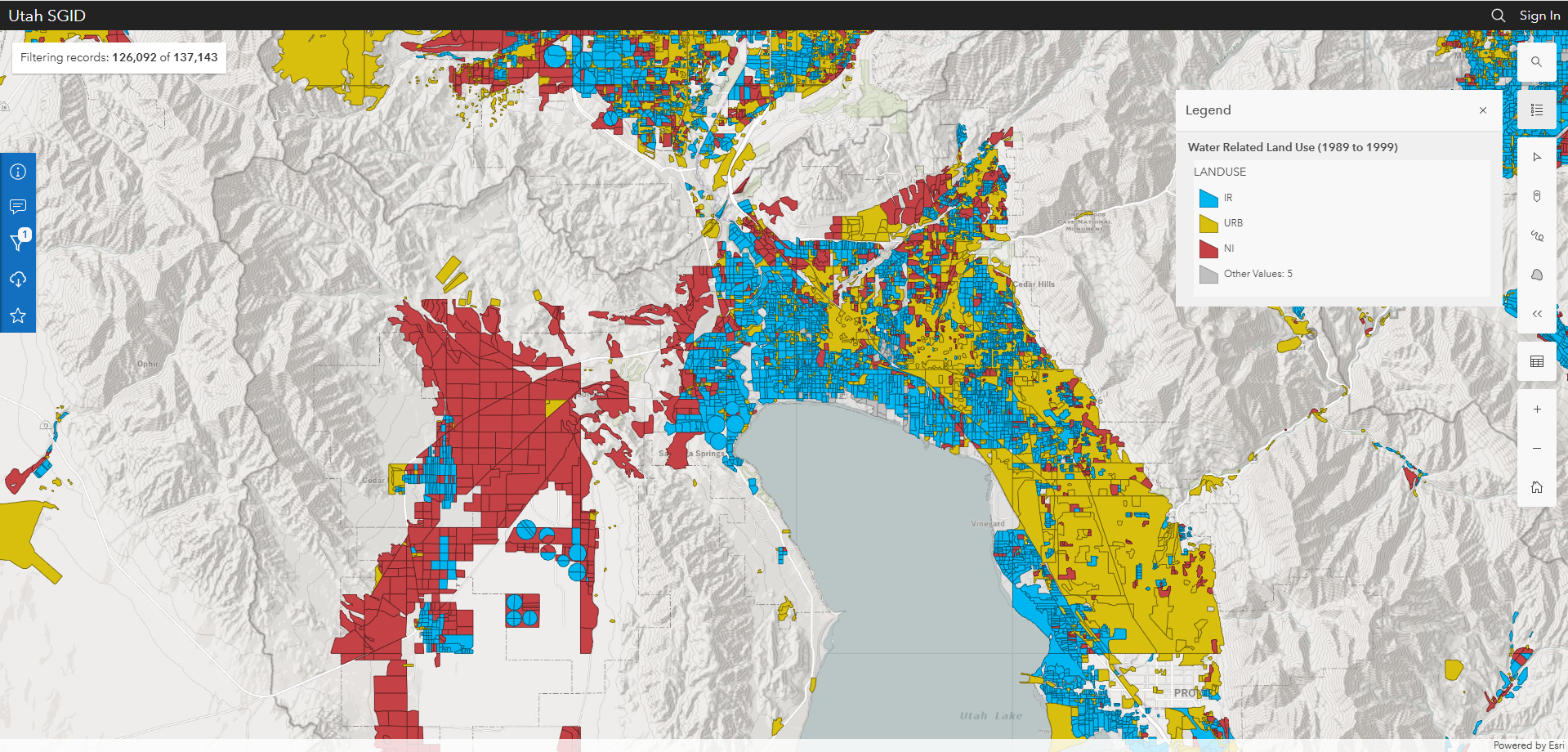

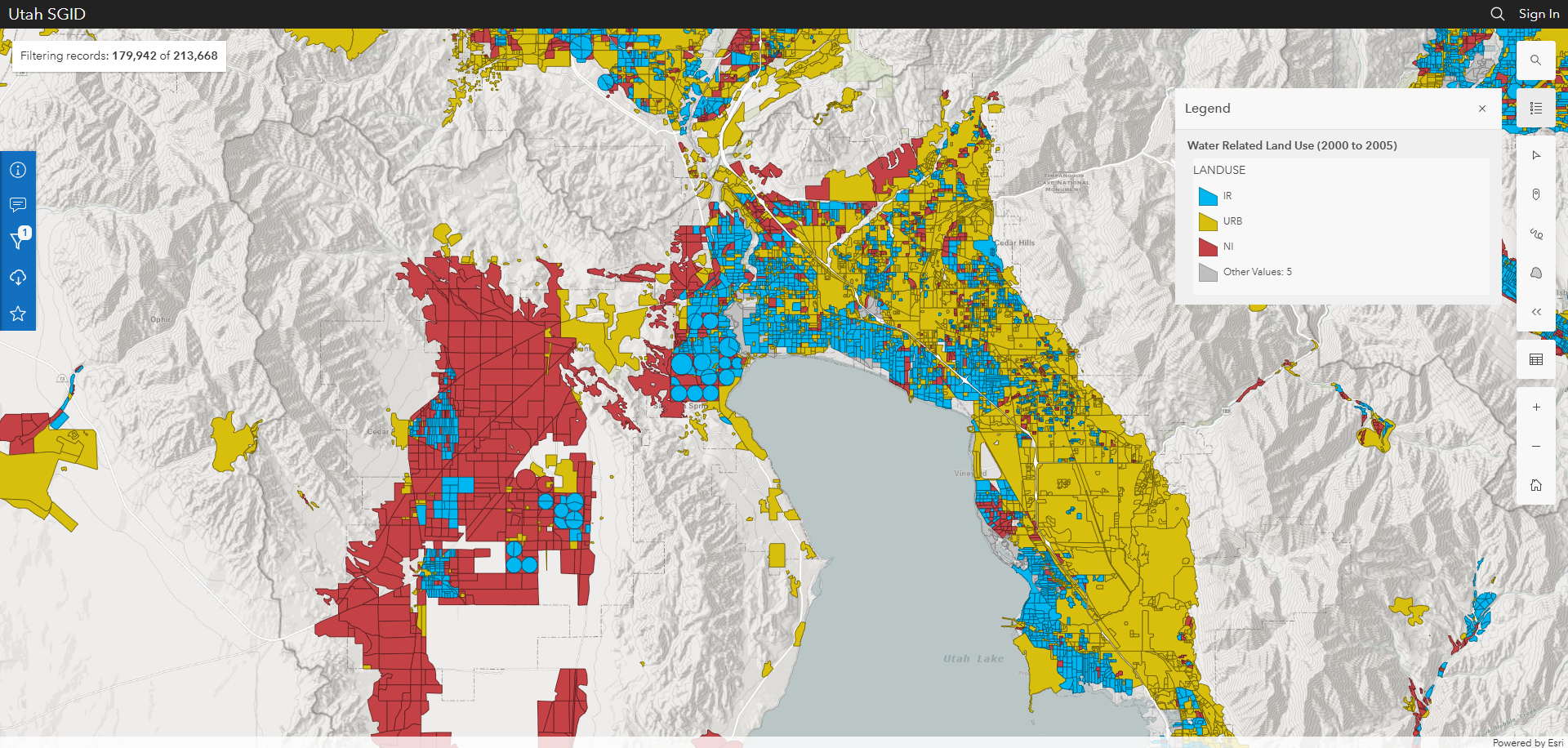

Those of us in the West are used to the phenomenon of suburban sprawl. This map is a good reminder that residential subdivisions do not typically encroach on undeveloped desert but rather on former agricultural land. The authors write, "Among the... newly urbanized areas during this period, about 38% was formerly irrigated agricultural lands, 12% was formerly non-irrigated agricultural lands, and about 50% was 'other,' a category consisting of mostly rangelands." I was surprised to learn that 50% of newly urbanized land did not come from former agricultural land, a statistic that is difficult to see on this map. It appears to me that most of those pink dots that appear out of nowhere are on the "Wasatch Back," a difficult area for agriculture that has seen much population growth in the last few decades. Perhaps the relatively small footprint of urban land means that it does not take many of those pink dots to bring up the percentage considerably.

Another finding from this paper is that there has not been a linear progression from ag land to residential. Looking at non-irrigated vs. irrigated ag land shows that there is a significant amount of conversion, in both directions, between these categories. What is non-irrigated agricultural land? Some farmers practice dryland techniques, especially for wheat. Wheat only represents about 1.6% of cash receipts in Utah as of 2020, compared to hay's 14.5%, but dryland wheat accounts for a significant percentage of that. But it is more likely that the non-irrigated ag land is pasture or that the farmer is letting that land lie fallow for whatever reason.

Why does this matter? One of the implications of the study is that urbanization fragments irrigated agricultural land, leading to changes in irrigation infrastructure and food production. Urbanites frequently wonder why farmers don't simply grow higher value crops that use less water. One of the reasons is that farmers are adapting to rapid changes on multiple fronts, and changing one's crop production requires investment. The climate is getting hotter and drier, and good ag land is getting developed for housing as the West continues to grow. These factors could influence farmers' buying up parcels of non-irrigated land, or investing in pressurized irrigation systems to convert that land for hay production, or letting irrigated land go fallow. Furthermore, the market infrastructure for certain crops may create additional hurdles. The safest bet for many is to grow alfalfa or keep pasture to supply the state's top agricultural commodities: beef and dairy.

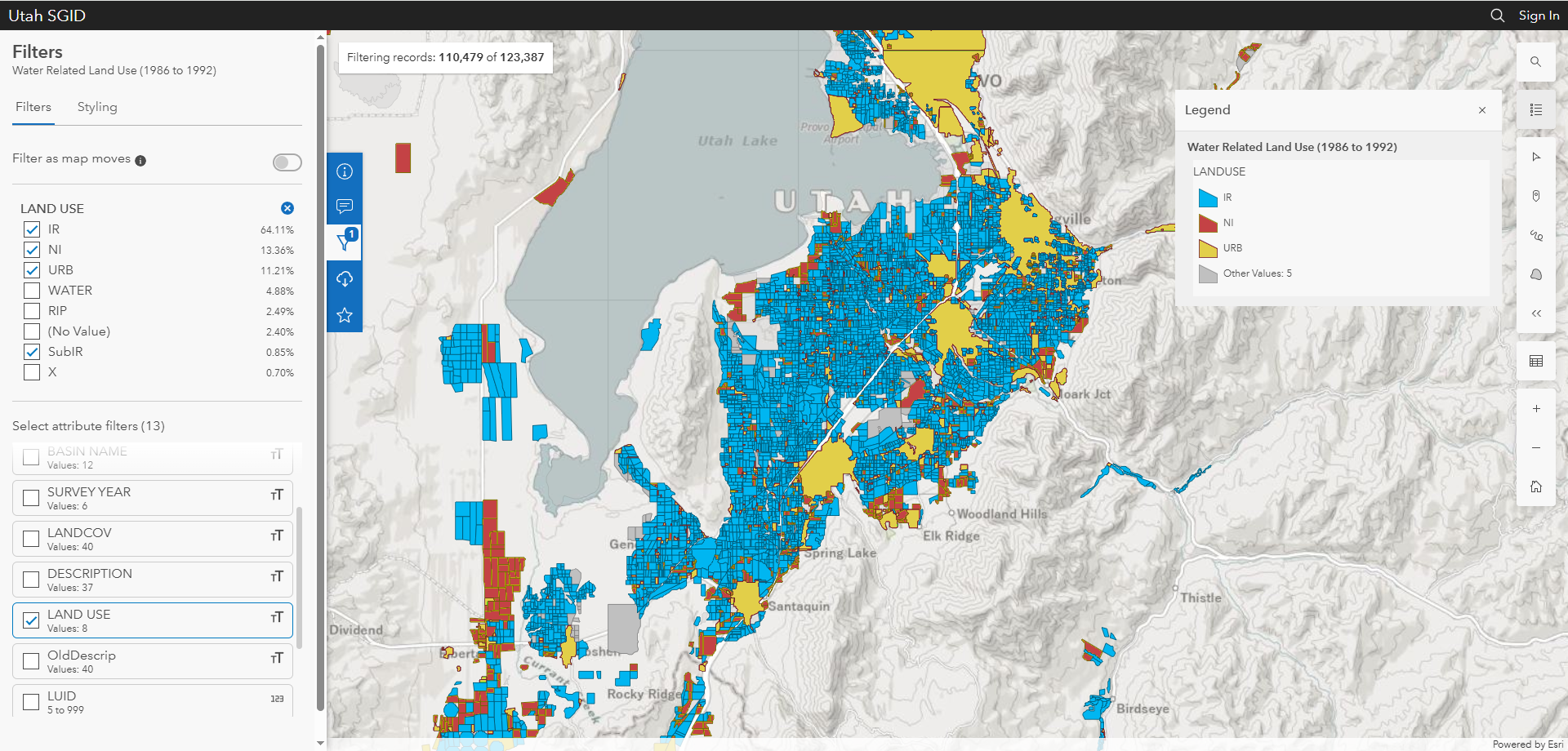

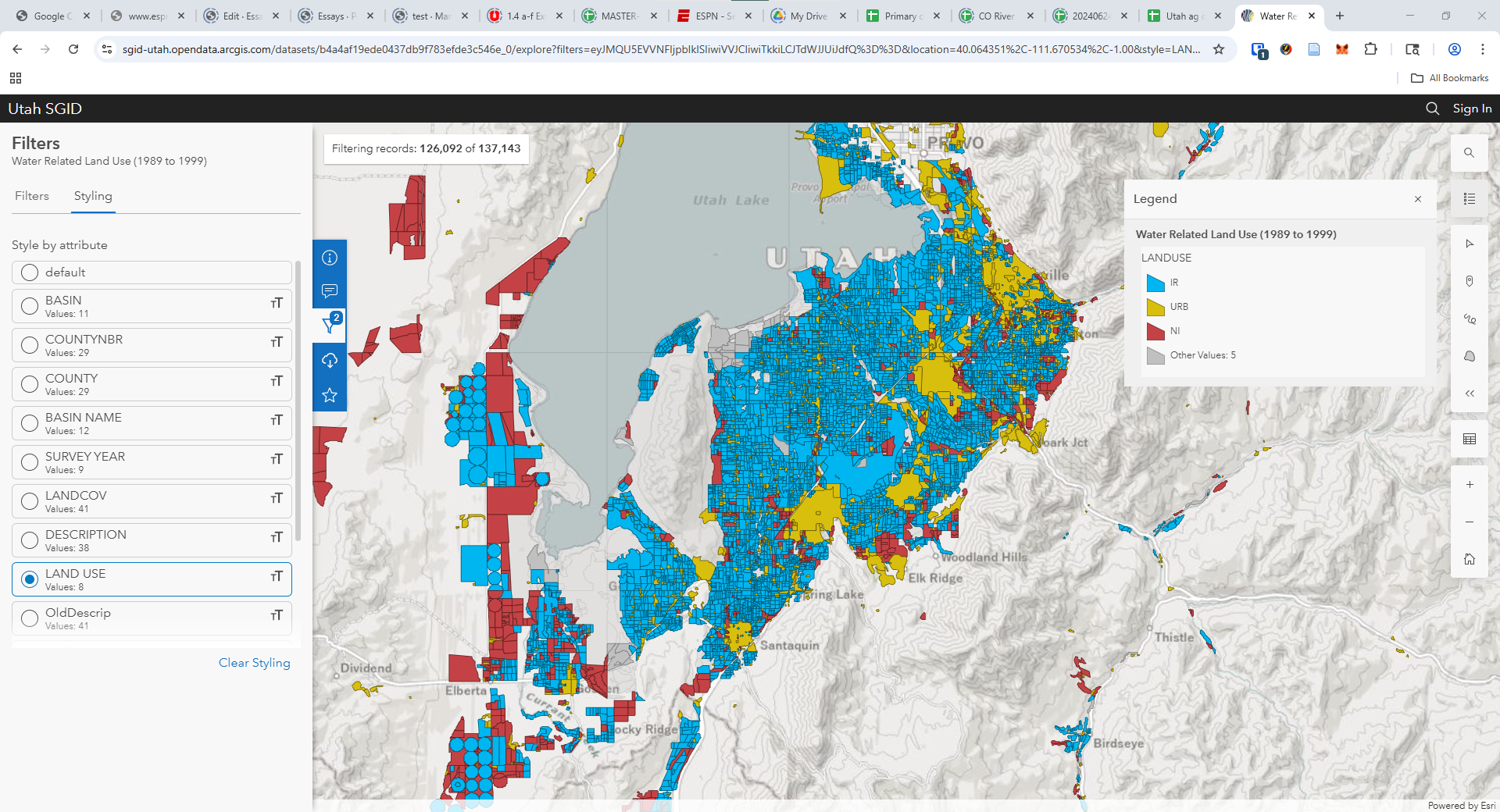

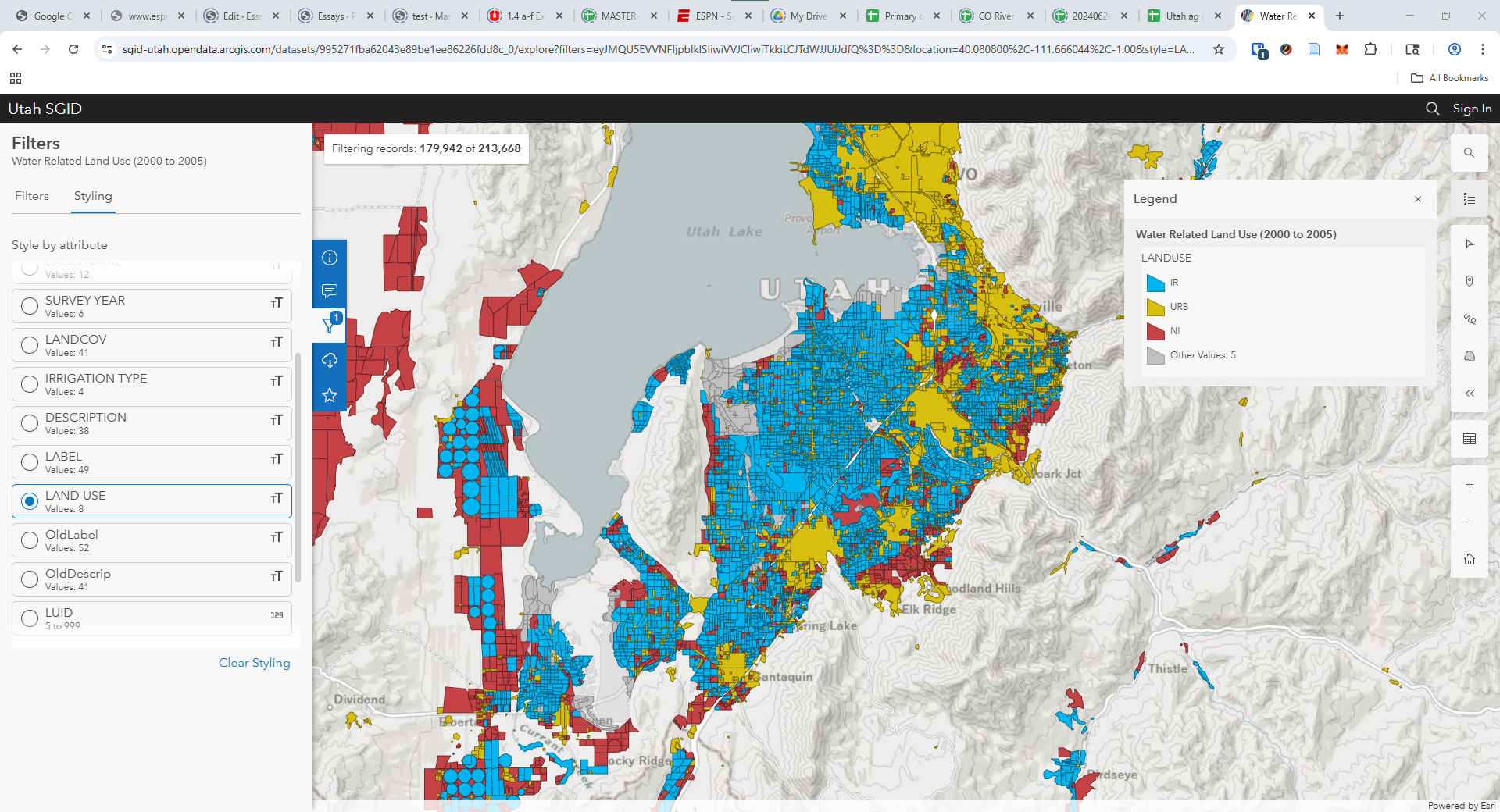

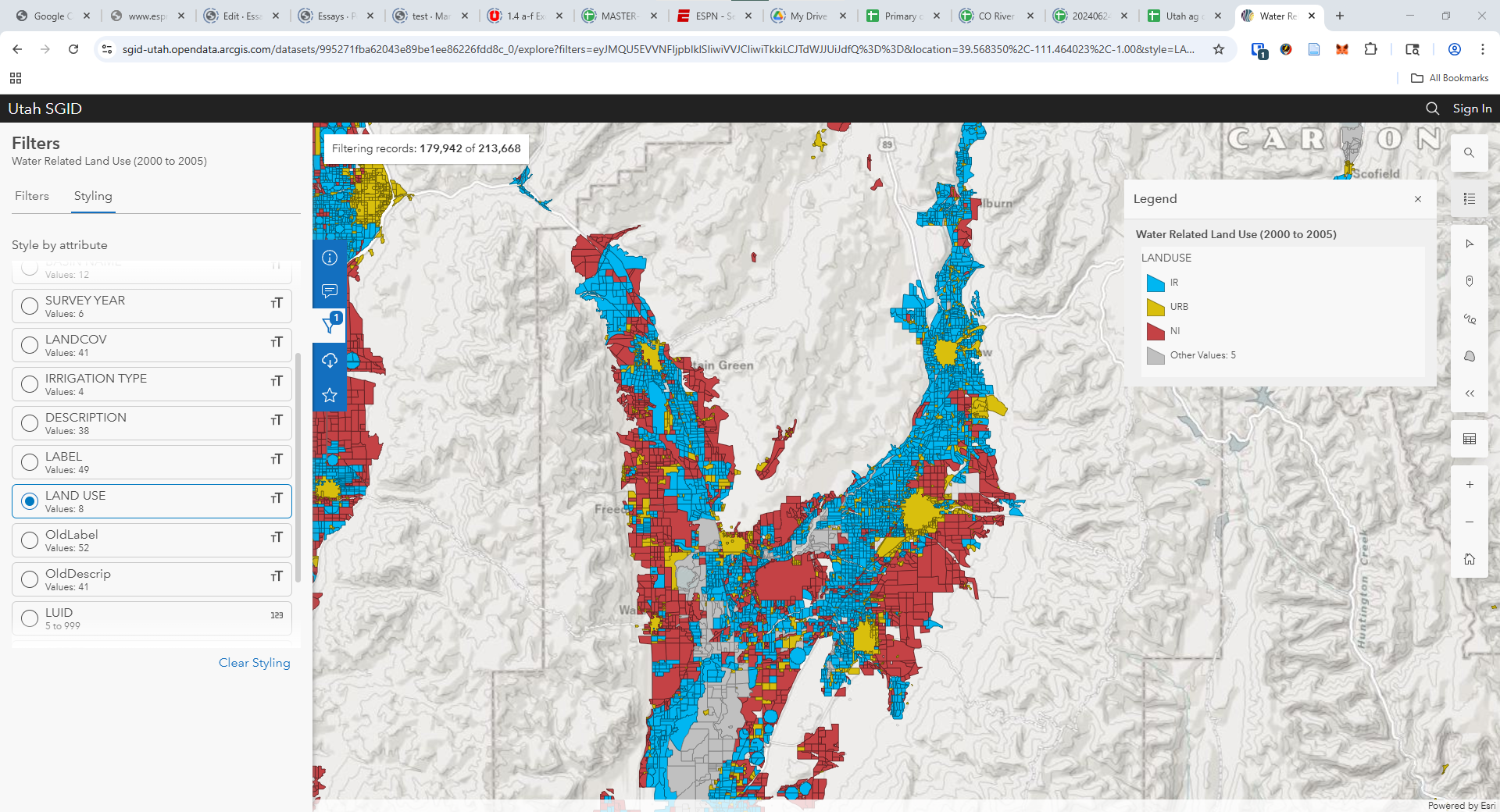

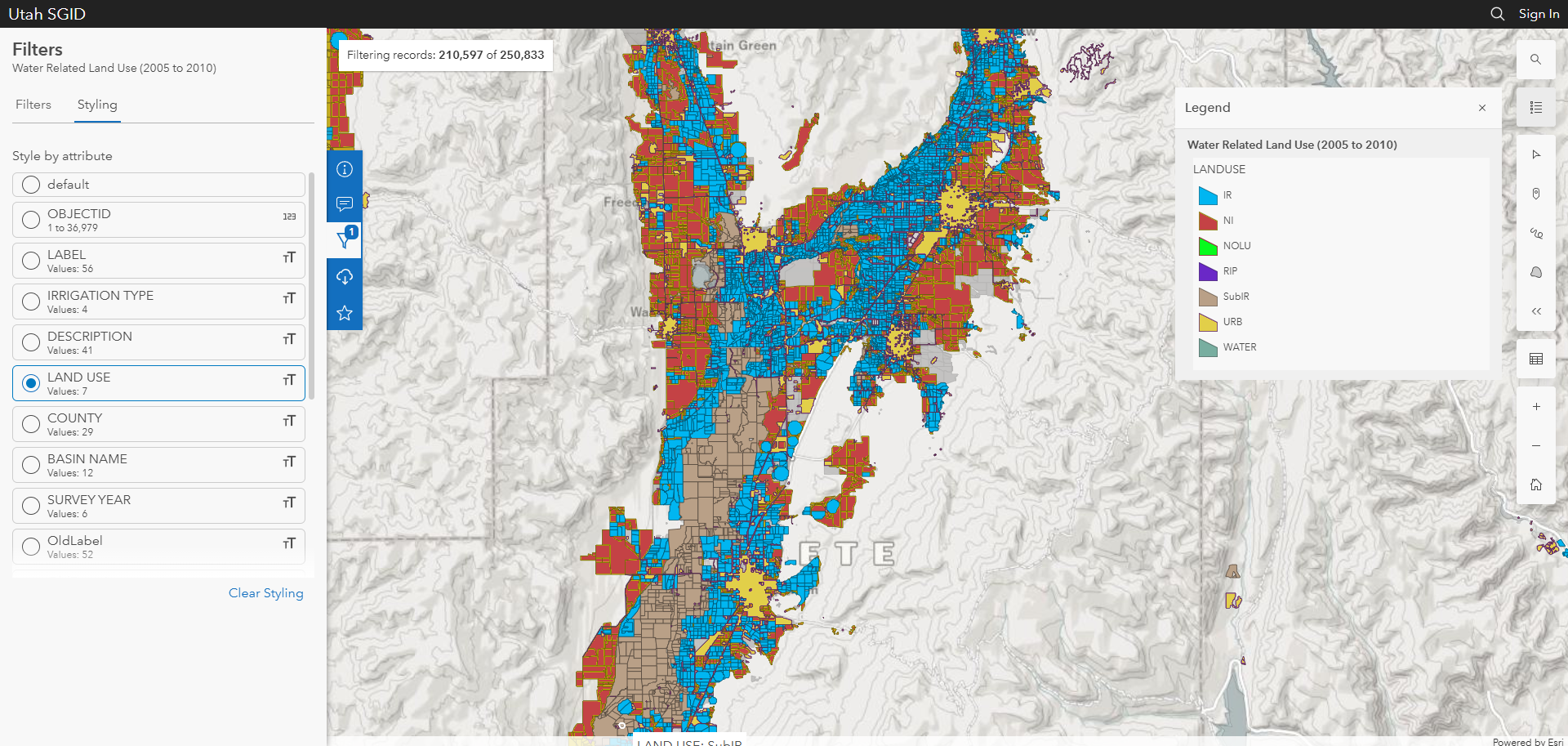

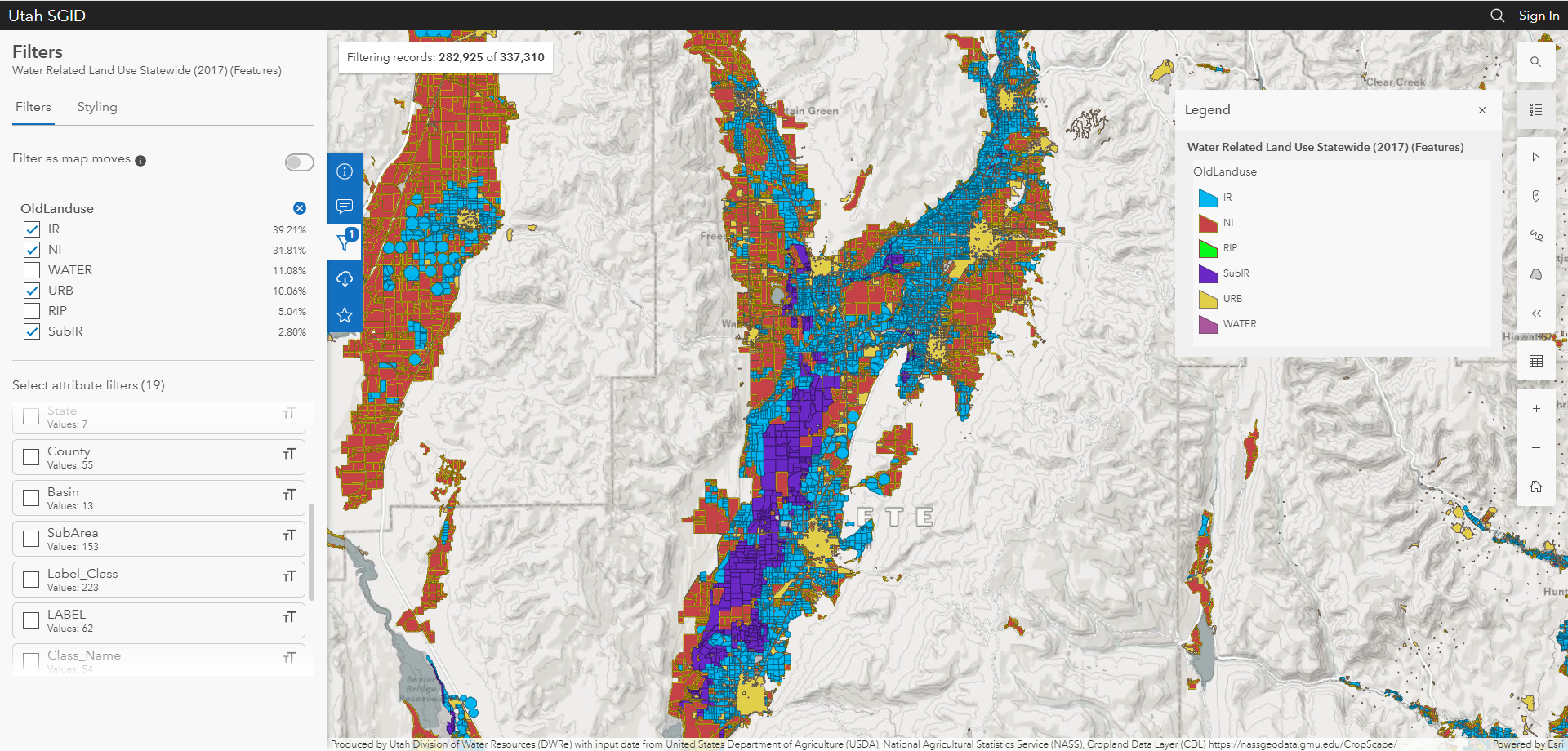

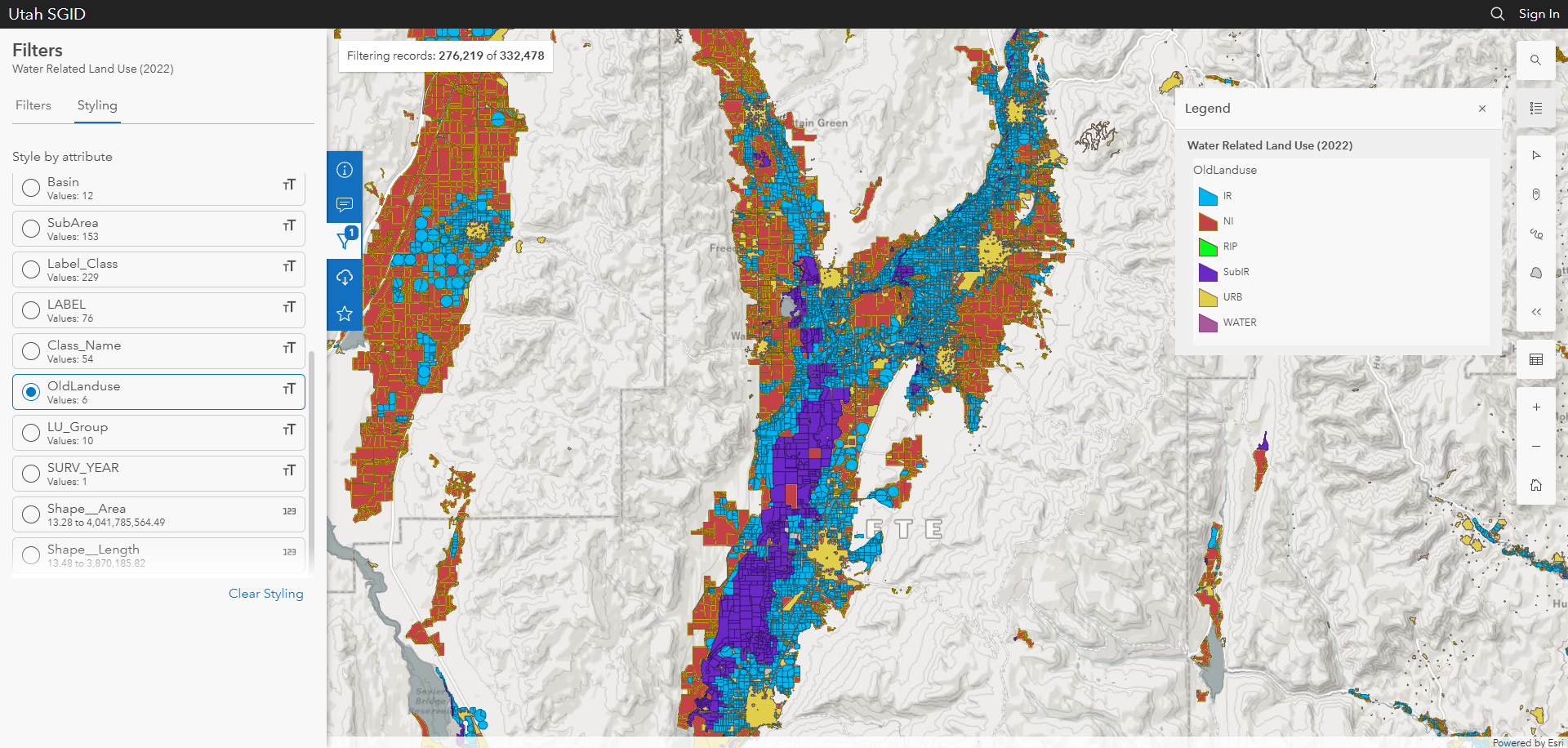

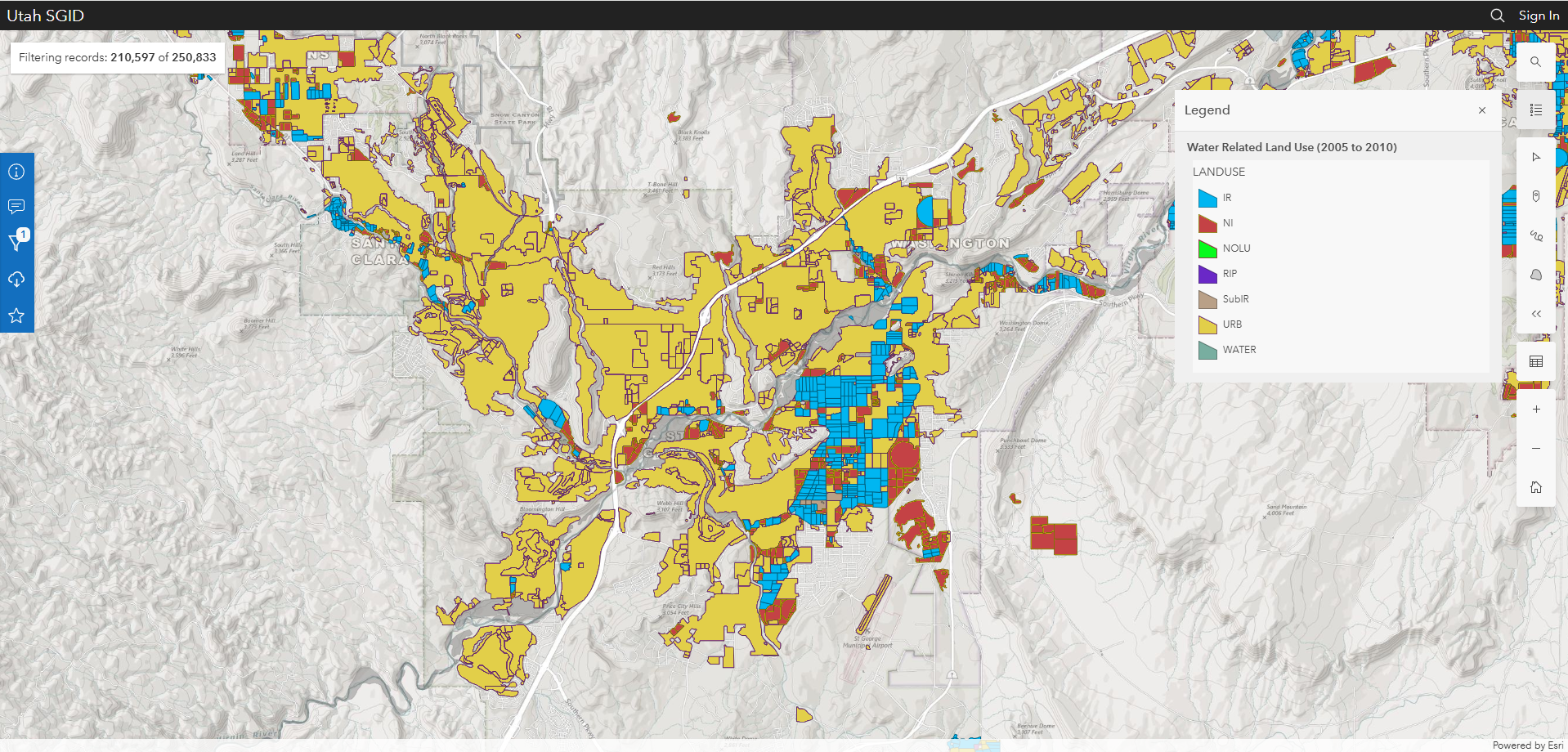

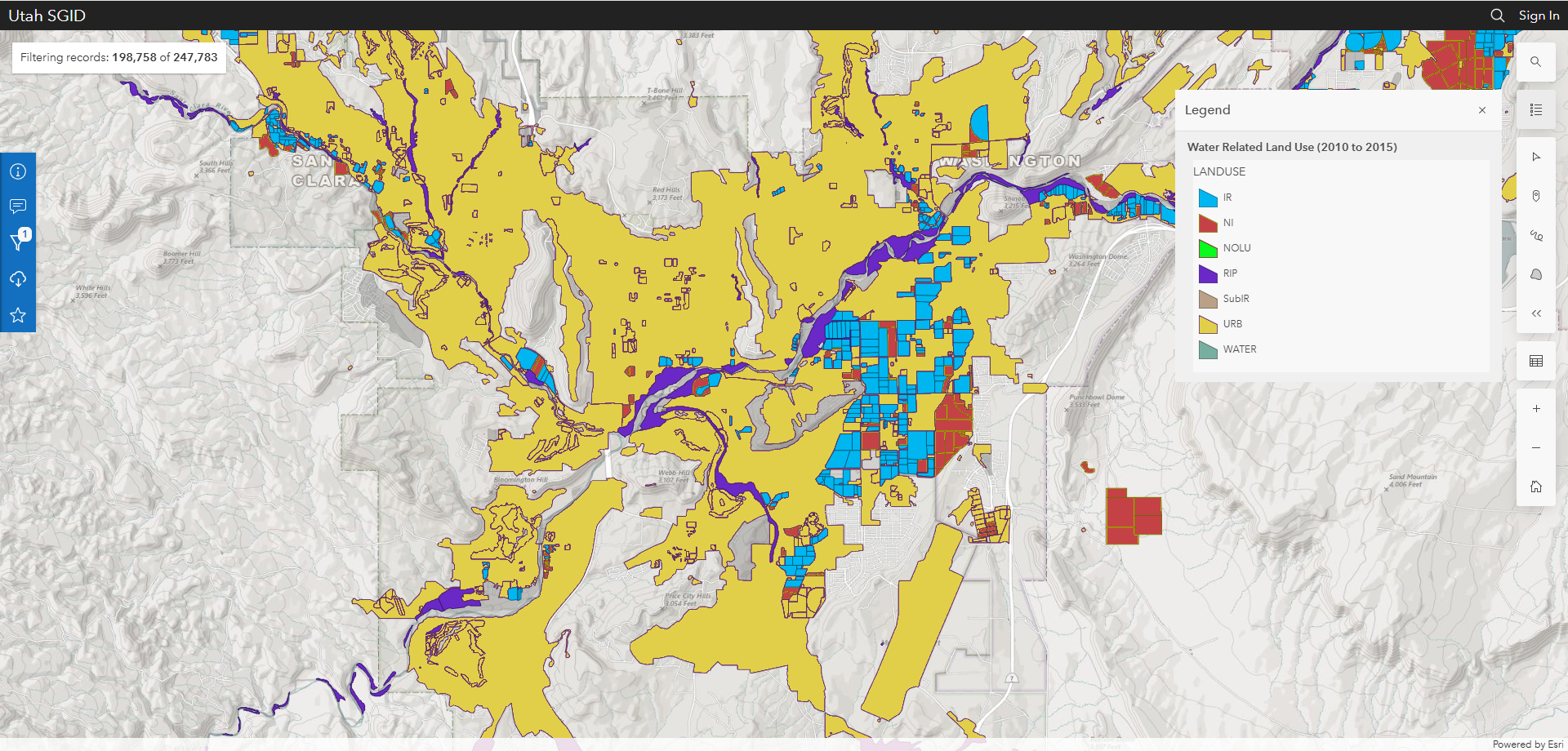

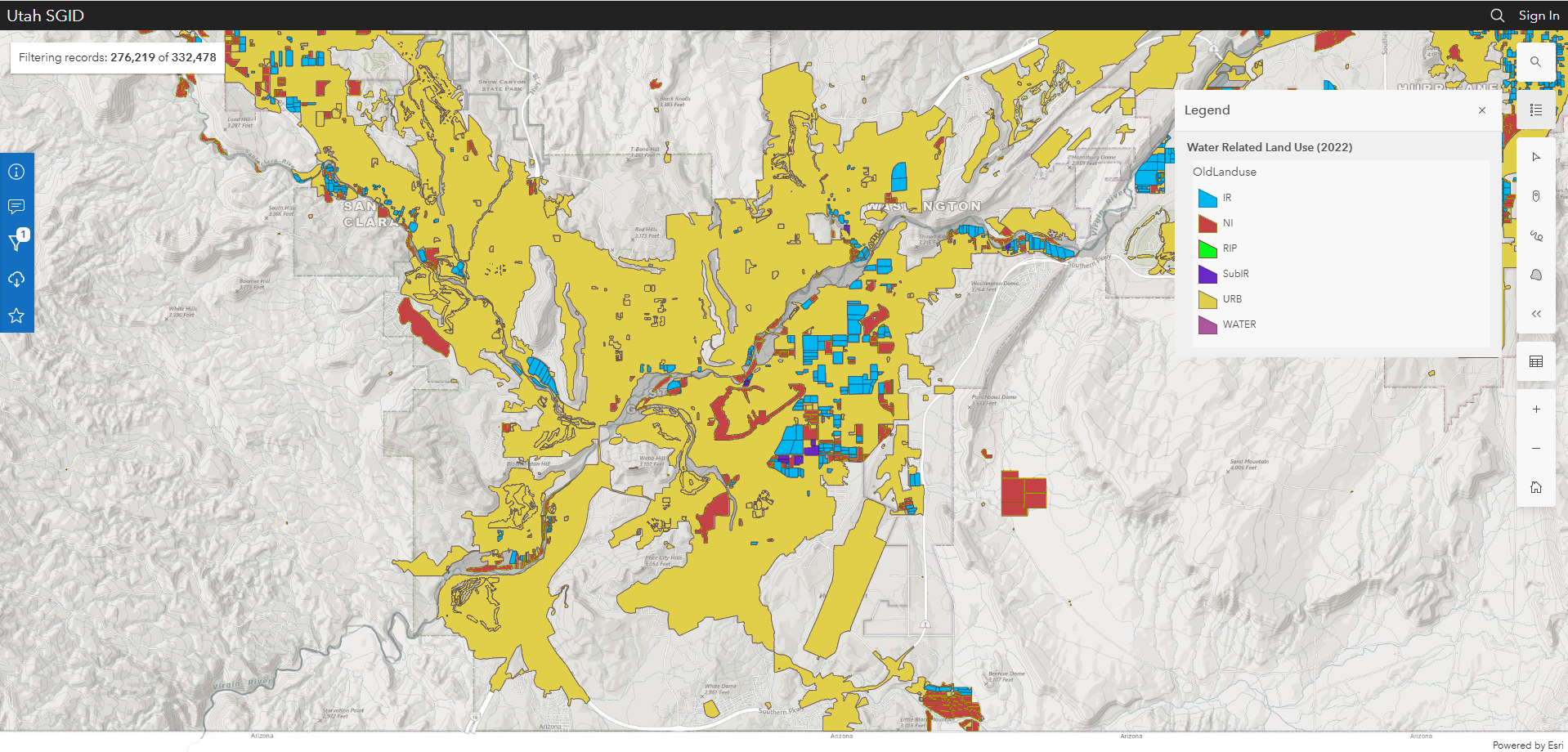

With that context, let's look at some GIS. Utah has a really nice online tool found here.

Bonus: Here is a subpar animated gif:

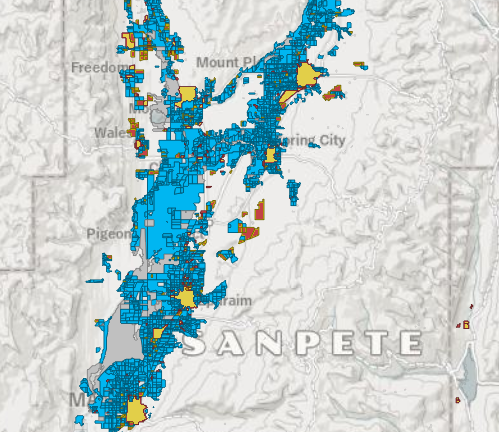

(Urban land is mustard yellow, in case that's unclear. Note: I edited the colors on some of these screenshots to be consistent over time.) Utah County seems to hew most closely to the pattern wherein agricultural land gets converted to urban land. We see that pattern in the Sanpete Valley too.

However, I was interested in what has been happening on the west side of Utah Lake, since there is urban development in Saratoga Springs that seems to bypass agricultural development. (It is worth noting that the urban land category includes industrial uses. Some of the isolated plots of urban land have not been developed into housing and seem rather unlikely to be anytime soon.)

I was also curious about Washington County as the fastest growing county in the state. It also lies outside of the valleys that the authors above included in their study.

We can see that urban land has been gradually filling in land in that wildland "other" category in St. George. While Washington County has some fairly substantial rivers, farmers have had difficulty in making the area into much of an agricultural powerhouse. Sandstone desert conditions are not great in the way of fertile soil, and the flooding of rivers poses a threat to cropland and irrigation infrastructure as much as drought does. But in recent decades, St. George has become an increasingly attractive destination for "snowbirds" and retirees. Between 2000 and 2020, the population of the metro area doubled, to 180,000 residents.

I don't know if I have a solid conclusion to all of this. I was curious about these patterns, and I was a bit surprised that so much urban development has taken place in non-agricultural land. But I also think it's notable that this is a bit of an exception. That is, in hot housing markets, that are not extremely distant from population centers, that have traditionally been hard for agriculture, you might expect to see housing developments go up on land that was just wild brush.